1.20 Riga’s Town Hall Square

Ilgvars Misāns

Edited by Jörg Hackmann and Mati Laur

Reflection of the Approach Toward the Historical Heritage of a City with a Chequered History

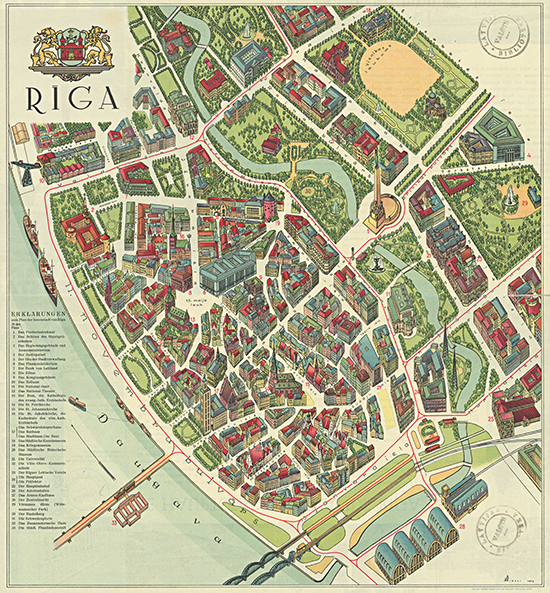

Since the Middle Ages, the square known as the Town Hall Square has been the economic and administrative centre of Riga, which was founded in 1201 in the eastern part of the Baltic Sea region, a city where the Germans were predominant up until the turn of the 20th century. Two splendid buildings – the House of the Blackheads, the brotherhood of unmarried foreign merchants and journeymen, and the town hall embodied the economic and political importance of the city on the Daugava. These buildings, which were remodelled several times over the years, along with the Roland statue adorned the well-designed square and presented a uniform setting until the World War II. However, already in the interwar period, when Riga had become the capital of the new nation state of Latvia, ideologically motivated changes were made to the appearance of the square. In an attempt to downplay the German influence on Riga, construction of a new city administration building was begun on western side of the Town Hall Square.

In the summer of 1941, during the advance of the German Wehrmacht, the square went up in flames; when the fires were extinguished, the buildings lay in ruins. As long as Riga was occupied by the Germans, it was clear that the most important historical buildings on the town hall square were to be rebuilt. Following the war, when the Soviet Union reasserted its power in Latvia, which had been annexed in 1940, policy-makers declared the House of the Blackheads to be a monument to a foreign knightly culture, which was fundamentally hostile to the Latvian people. The ruins of the structure were demolished in 1948. Six years later, the remains of the town hall were removed and the Roland statue was moved to the city depot.

A public flower garden with benches was installed in the middle of the square. Around the garden, buildings of importance to the capital of Soviet Latvia were erected, reflecting the technical capabilities and aesthetics of the period – the Polytechnic Institute building (currently the Technical University) and a row of five-storey terraced houses employing pseudo-medieval and pseudo-modern gables in an attempt to fit in with the surroundings of the Old Town. Built in 1971, the Museum for the Red Latvian Riflemen (currently the Occupation Museum) - the heroes of the Bolshevik regime in Russia after 1917 – placed the mark of Soviet ideology on the square.

A sizeable number of both Latvian intellectuals and the general population regretted the loss of the historical town hall square already in Soviet times, and after the restitution of Latvia’s independence in 1990/1991, rebuilding the House of the Blackheads became a high priority. In December 1999, the newly reconstructed House of the Blackheads was dedicated as a museum, event venue and concert hall. Many of Riga’s inhabitants viewed it as symbolic of the return of Latvia and its capital to the western European community of values. At the same time, the nearby Schwabe House and the Armoury of the Riga City Guard (Blue Guard House) were rebuilt and restored to their former appearance. The new Riga City Council building followed in 2003. Here, only the historic façade was restored; the interior was modernised. The copy of the historic Roland statue was also put up in the square again. The present and most recent history are represented in the Town Hall Square by the new building of an upscale hotel and a multipurpose office building (Kamarin’s House), whose architectural and aesthetic quality was the subject of much criticism.

Jānis Āberbergs, Head of the Cultural Department of the Riga City Council, on the role of individual nationalities in the Latvian capital Riga (1932).

- The year 1920 was the beginning of a new era in the life of Riga. The government of the new, independent Latvia drew on the entire population of Latvia. While the nation’s capital was once German, then Russian, it is now Latvian. Riga is Latvian only because Latvians constitute the majority and Latvian is the common vernacular in the city. Riga is a democratic city and each group of inhabitants is represented in the city’s self-administration proportionate to its number and prominence.

- - J[ānis] Āberbergs. “Rīgas pilsētas vesture” (History of the City of Riga). In: Rīga kā Latvijas galvas pilsēta. Ed. by T[eodors] Līventāls, V. Sadovskis. Riga, 1932. P. 5-56. Quote: p. 55-56.

Mayor Roberts Lapiņš on the necessity of changing the cityscape of Riga (1937).

- The President and the government have stressed a number of times the need to change the Old Town in accordance with the spirit of the times, in particular the quarter on the Daugava. The city must not forget this responsibility called for by the current era, and the city must bear in mind this great task – to give our capital a new look.

- - Quoted from Pārsla Pētersone. “Rīgas pilsētas administratīvās ēkas” (The administrative buildings of Riga’s City Government). In: Rīgas pārvalde astoņos gadsimtos. Riga, 2000. P. 279.

The responsible Riga city architect Voldemārs Šusts on the failed restoration of the Town Hall Square (1967).

- The idea of a complex reconstruction was not realised, even though the necessity was obvious. The ruins of the House of the Blackheads were eliminated, the Town Hall demolished […] Such indifference to the architectural monuments of Old Riga, which was in opposition to the opinion of the majority of the architects, was no coincidence: behind it was the nihilistic theory of the appreciation of our architectural heritage. In fact, the common view of the German “cultural institution” was adopted, and this held that the true creators of all cultural values – including the architecture – were the German immigrants. That led to the conclusion that the architecture of Old Riga expressed foreign, hostile ideology! Why should it be restored, preserved, maintained?

- - Voldemārs Šusts. Diskusija turpinās (The discussion continues). In: Māksla, 1967, No. 1, pp. 18-19.

Vice President of the Latvian Academy of Sciences, Jānis Stradiņš, on the fate of the House of the Blackheads (1995)

- The Blackheads House, over the times, had grown into a symbol of Riga. To be more precise, it was the Town Square ensemble with the Blackheads House and the outline of the tower of the St Peter’s church – the visual centre of the Baltic metropolis, without which Riga was not quite its true self. [...]

- The awakening of our nation, the resumption of Latvia's independence, the re-evaluation of our historical heritage have taken us to the outset, to the search, of the ways to reanimate Riga. The 800th anniversary of the city in 2001 is a good additional incentive to these intentions. The scheme, which only ten years ago seemed impracticable, to reconstruct the Blackheads House and, later, also the whole of the Town Square ensemble, has been launcher. [...] Public at large has accepted the idea, there is only shortage of funds – Latvia is still poor, so is the ancient Hanseatic League town Riga.

- The Blackheads House should be considered not only as an architectural monument which had developed in long and complicated succession of epochs and styles, thus acquiring its inimitable image, the work of no single architect or result of single century. The Blackheads House is also a monument to the social, cultural and musical activities of ancient citizens of Riga. [...] Within its walls important historical events had taken place [...]. The Blackheads House is another rehabilitation of the Baltic Germans, their remarkable contribution to Riga, the Hanseatic League, Eastern Baltics, Latvia. [...]

- It will become an attribute of eternal Riga; it will visually confirm Riga's affiliation to Western Europe and will be evocative enterprising spirit of ancient Riga’s young traders, full of mettle and zeal – also on the far-off Eurasian roads.

- It is not only a matter of mere physical reconstruction of the architectural monument. The p h i l o s o p h i c a l meaning of the restoration of the Blackheads House is the resurrection and inheritance of the traditions. [...]

- And the future citizens of Riga will wonder how we could have lived in the city for more than fifty years without the Blackheads House.

- - Jānis Stradiņš. “Über das Schicksal des Schwarzhäupterhauses und dieses Buch”. In: Melngalvju nams Rīgā. Ed. by Māra Siliņa. Riga, 1995. pp. 13-14.

Photos

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Which power relationships and political changes have characterised the history of Riga from its founding to the present day?

- How did the chequered history of the city influence the appearance of the Town Hall Square?

- Which ideological principles and values shaped the approach toward the historical structures on the Riga Town Hall Square since 1918?

- How would you evaluate the current appearance of the Riga Town Hall Square? What message does it send to our contemporaries?

Further reading

- Jānis Krastiņš. Riga Town Hall Square: Riga Town Hall Square today, the Town Hall Square in the mirror of recent history, the Statue of Roland, buildings surrounding Town Hall Square. Riga [2010]. (In German: Jānis Krastiņš. Riga, der Rathausplatz: der Rathausplatz heute, der Rathausplatz im Spiegel, der jüngsten Geschichte, die Rolandstatue, Gebäude rund um den Rathausplatz. Riga [2010]. In Russian: Янис Крастиньш. Рига, Ратушная площадь: Ратушная площадь в наши дни, Ратушная площадь в зеркале новейшей истории, статуя Роланда, здания вокруг площади. Рига [2010]).

- Melngalvju nams Rīgā = Das Schwarzhäupterhaus in Riga = The Blackheads House in Riga. Ed. by Māra Siliņa. Riga [1995].

- Andreas Fülberth. Riga. Kleine Geschichte der Stadt. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna, 2014.

- Jörg Hackmann, “Metamorphosen des Rigaer Rathausplatzes, 1938-2003: Beobachtungen zur Rolle historischer Topographien in Nordosteuropa” (Metamorphoses of the Riga Town Square. Notes on the role of historical topographies in North Eastern Europe). In: Wiedergewonnene Geschichte. Zur Aneignung von Vergangenheit in den Zwischenräumen Mitteleuropas. Ed. by Peter Oliver Loew, Christian Pletzing, Thomas Serrier (Veröffentlichungen des Deutschen Polen-Instituts, 22). Wiesbaden, 2006. Pp. 118-141.