1.21 War and Peace in the Baltic Sea Region

Jörg Hackmann, Anders Fröjmark, Mati Laur

"Dominium maris Baltici” and “Sea of Peace”

Since the end of the Cold War, the Baltic Sea region has been perceived as a region shaped by a common history and the wish of the peoples on its shores to live in peace and to be masters of their own political, economic and social decisions. However, the fact that the mutual relations between the states on the Baltic rim are shaped not by violent conflicts but by peaceful contacts, is a rather recent and also precarious phenomenon. Today, there is a substantial effort to ensure peace, democracy and prosperity in future, but how can one refer to a common history, when this history is shaped by war, genocide, occupation, repression, plundering and other terrible events? Shall one just declare history to be past perfect that is to overcome or to ignore because it is unrelated to our present and future?

The German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin put this dilemma in his interpretation of the painting Angelus Novus by Paul Klee:

- A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

The following aspects and examples will give some food for thought for the discussion of approaches to past aspects of violent history in the Baltic Sea Region that were shaped by dialogue and reconciliation and not reinforced nationalism.

Changing commemoration of war

Even if the time of wars and their traumatic consequences for soldiers as well as the civilian population in the eyes of the younger generations seems to be a thing of the past, there are still many people who vividly remember the World War II and its horrors.

War and peace, however, shaped the life of almost all previous generations in the Baltic region. When remembering this today, the horrors have already faded into the background, and increasingly we see the battles of previous centuries as an occasion for reenacting and reliving earlier times. This happens, for instance at the Marienburg / Malbork commemorating the battle of Tannenberg / Grunwald / Žalgiris 1410. More recently, also reenactments of the World War II have been staged (see Meelis Muhu’s documentary: Let’s play war - https://vimeo.com/163809103).

Or we are amazed by the “Vasa” in the museum with the same name in Stockholm. When built, the ship was the biggest navy vessel to date, but it didn’t make it to its mission area at the Baltic coast of Poland because it capsized and sank during a test sailing in the harbour of Stockholm in 1628. There it remained in the mud for more than 300 years, until it was rediscovered in the late 1950s and salvaged in 1961.

Today, shipwrecks and cannons of that time are mostly cultural relics. Against this background, one might understand that the Latin term of Dominium maris Baltici – dominion of the Baltic – does not connote the horror of previous wars but historical communalities around the Baltic.

Dominium maris Baltici

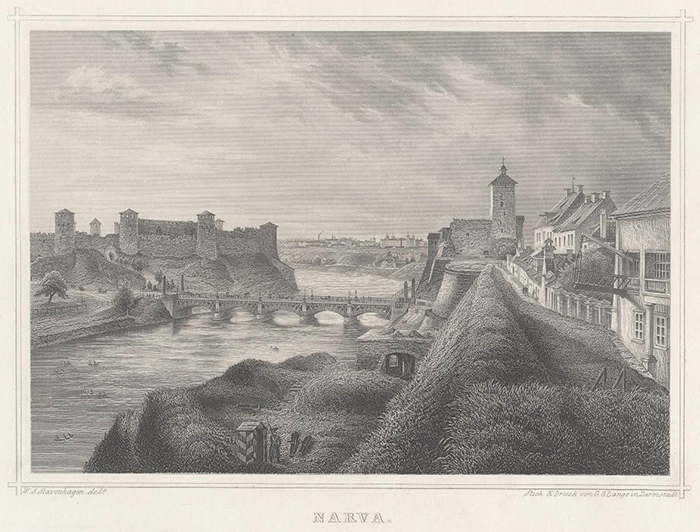

What was at stake in this conflict of Baltic powers? For many centuries, control over the sea was a decisive factor of power. A special role was taken by Denmark which controlled the Öresund and thus the passage from the oceans to the Baltic and vice versa. The Sound dues were a major source of revenue. The Danish power position was challenged by Lübeck under the leadership of Jürgen Wullenweber in the 1530s, but the failure of this challenge highlighted the decline of the Hanseatic towns as a political factor against the new territorial states. At the same time, Sweden tried to strengthen its power position in the Baltic region and Russia also demanded access to the Baltic. The fortress of Ivangorod, erected by Ivan III in 1492 opposite of Narva, highlights these tensions.

Thus, conflicts over the Dominium maris Baltici shaped the Baltic region for almost 200 years. Sweden was in the centre: it waged war against Denmark, the Catholic emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Poland-Lithuania and also against Russia. For a time, Sweden controlled large parts of the Baltic rim. The consequences of these wars were devastating: Often, whole regions were plundered, epidemics and hunger decimated the population in addition to those who died in the fighting. In Poland, the Swedish invasion of 1655 is remembered as “Deluge“.

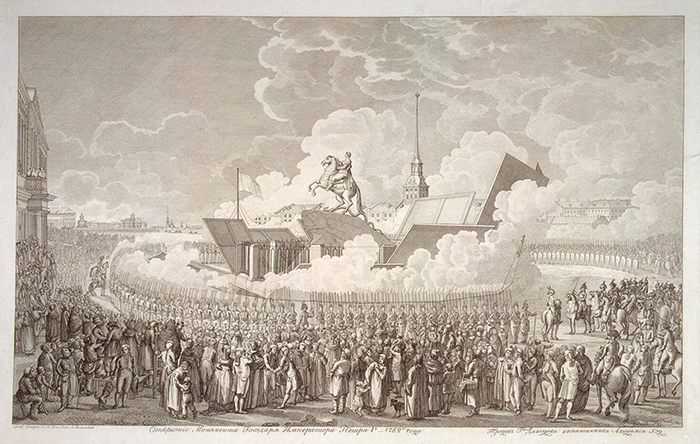

At the end of this struggle for dominion, Russia rose to become a great power on the Baltic, and with the new capital of St Petersburg at the mouth of the Neva river, the largest city in the Baltic region today was founded in 1703. In the 18th century, Russian foreign policy then developed the idea of a peaceful Baltic region, the “calm of the North”, albeit under the condition of Russian control of the region.

War and Peace in the 19th century

However, the armed conflict continued. In 1808/09, Russia conquered Finland, which until then had been a part of the Swedish state, and Russian troops moved across the frozen Baltic Sea and threatened Stockholm. In response, Sweden was convinced that a peaceful policy based on neutrality was better for the nation than ongoing wars.

However, the Russian “Calm of the North” could not be maintained permanently. During the Crimean War of 1853–1856, British warships advanced as far as Reval / Tallinn, then part of the tsarist empire. After the peace agreement, Russia had to give up the destroyed fortress of Bomarsund on the Åland Islands outside of Stockholm, and the islands from that time onwards received a special demilitarised status in the region.

At the end of the 19th century, Russia and Germany built and stationed large fleets on the Baltic rim: Kiel and Mürwik (modelled after the Marienburg) on the German side, Libau/Liepāja and Kronstadt off St Petersburg on the Russian side were important bases.

The 20th century

During the World War I, the Scandinavian kingdoms declared themselves neutral, and Sweden was able to maintain this position also during the World War II.

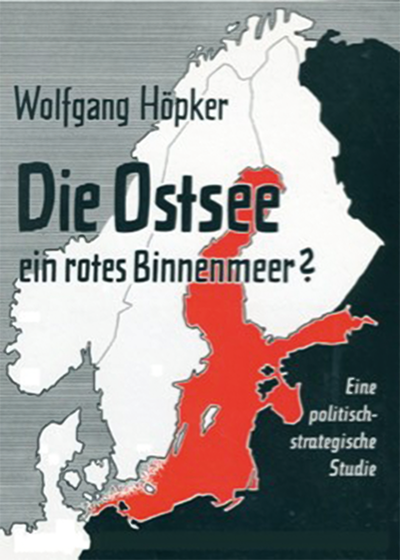

After 1945, the notion of “Calm of the North” returned in the slogan of “Sea of Peace”. Not only did it express people's desire for a peaceful future - which was widespread for good reasons after the experiences of the war - but it was also an ideological argument during the Cold War.

According to this notion, the socialist countries were peaceful, whereas the capitalist states were allegedly belligerent. Conversely, some political circles in the West conjured up the danger of a “Red Sea”.

NATO and the Warsaw Pact prepared themselves for a new war in the Baltic region. Only a few years after the end of the World War II, there were plans for a German navy which would not only defend the western Baltic Sea against a Soviet attack but would also carry out landing manoeuvres on the eastern Baltic rim. Conversely, planning in the GDR and Poland envisaged occupying Denmark as quickly as possible and then advancing into the North Sea. Just how tense the situation was was illustrated by the multiple incursions of Soviet submarines into Swedish territorial waters, such as the “Whiskey-on-the-rocks” incident in 1981, when a submarine ran aground off Karlskrona.

There were numerous military restricted zones, especially in the Soviet Baltic regions: the Kaliningrad region was difficult to access even for Soviet citizens, and Western foreigners were not allowed to spend the night in Tartu because of the proximity to the military airport. In addition to military dominance, there was strict surveillance of the Baltic coastline from the GDR to the Soviet Union in order to prevent escape attempts across the sea: Many beaches were raked at night to make footprints visible.

There were only few peaceful contacts, for example, in ferry lines across the East-West border; where they existed, they often led via Finland, which occupied a special position between East and West.

The last phase in the military strategic planning was the Mukran ferry port on the island of Rügen, which was completed in 1986 and provided the GDR with a direct rail link to Memel/Klaipeda in the Soviet Union. This made it possible to transport military material between the GDR and the Soviet Union bypassing Poland. With the emergence of the Independent Trade Union Solidarność in 1980, the GDR leadership feared that the Polish protest against the socialist regime could also spread to the GDR.

Freedom and Peace

While during the Cold War, freedom and peace were concepts of struggle in the East-West conflict until 1989, this changed with the protests from Tallinn to Leipzig at the end of the 1980s. The “singing revolution” in the Baltic Soviet republics symbolised this epochal turning point in the Baltic region. The Latvian documentary film director Juris Podnieks documented the spirit of optimism of those years in the film Krustceļš (Homeland) of 1988.

After the end of the socialist regimes, the first interest of the Baltic States from Germany to Estonia was the withdrawal of Soviet troops and the dismantling of their military facilities. Furthermore, the foreign political priority of the states from Poland to Estonia was to join NATO as protection against a renewed threat from Russia. The neutral North European states of Finland and Sweden, in particular, have attempted to define security in the Baltic Sea region not only through military alliance systems, but also through security policy dialogues and confidence-building measures.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- What does Benjamin’s view of history imply for interpretations of the history of the Baltic Sea region?

- Discuss the positive and negative aspects of military reenactments.

- Which role do the battles mentioned play in your national history?

- What could change in the perception of these battles, if you take a Baltic (or a global) perspective?

- Discuss strategies of reconciliation between former national enemies.

- Watch Meelis Muhu’s film “Let’s play war” (2016) and discuss the reflections on war in this documentary.

Further reading

- Kristian Gerner and Klas-Göran Karlsson. Nordens Medelhav. Östersjöområdet som historia, myt och projekt (The Mediterranean Sea of the North. History, myth and project of the Baltic Sea region). Stockholm, Natur och Kultur, 2002.

- Andres Kasekamp. History of the Baltic States. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Michael North. The Baltic: A History. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2015.