1.6 Marienburg/Malbork

Eugen Kotte

Edited by Janet Laidla and Malgorzata Dabrowska

A Symbol during Times of Change – A Place of Remembrance in Europe

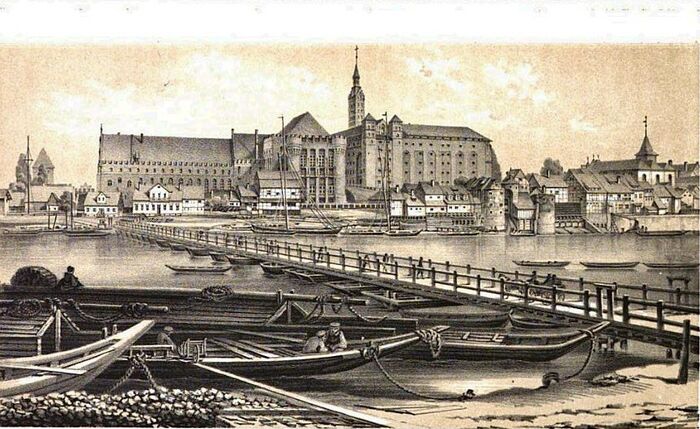

Marienburg (or the Castle of St Mary) in Poland, Europe’s largest castle, has had various owners over the course of the centuries: It was first commanded by the Teutonic Order, then by the Polish kings and later by Prussian Germany. After 1945, it became property of the Polish state. This castle functioned as a national symbol in various ways and for different purposes, but today it is a beacon of remembrance in Europe for all visitors to savour.

A Medieval Convent and Border Stronghold

After the Teutonic Order (initially the Knights of the House of the Holy Mary in Jerusalem) had answered the call to take up arms against the pagan Prussians, the building of the first part of the Marienburg (castrum sanctae Marienburch) began in 1276. This initial part of Marienburg, which has been known as the ‘High Castle’ since the 16th century, was situated in the western borderlands of the burgeoning Teutonic Knights’ State where it also served as a fortification in this part of their territory. The Knights first used the castle as a convent in 1280 under the tutelage of Commander Henry of Wilnowe. By 1300, the building was completed, almost to its present form, as a castle and convent in the monastic style of that period. The castle was consecrated as the Castle of St Mary, in honour of the Mother of God and the Patron Saint of the Teutonic Knights. After the Grand Master of the Knights had transferred his seat from Venice to Marienburg, the High Castle continued to function as a cloister, which in principle only members of the Order could enter.

The Seat of the Teutonic Order

Even after the seat of the Teutonic Order had been moved to Venice following the fall of Acre in Palestine in 1291, it still seemed to be in danger when the senior members of the Order were charged with heresy in 1307. As a result, the Grand Master, Siegfried von Feuchtwangen, decided to move to Marienburg in 1309 after the Knights had conquered Pomerelia, but it was his second successor, Werner von Orseln, who made the castle a chancellery and administrative centre of the State of the Teutonic Order. The growing significance of the strategically located castle, which served as the central gathering point for the most important bearers of high office in the Teutonic Knights (the commanders) together with its increasing economic importance as a centre of revenue coincided with its decline as a military base. However, the impressive fortifications - added during the 15th century under the new Grand Master, Heinrich von Plauen, following the Polish-Lithuanian victory over the Knights at the battle of Grunwald/Tannenberg in 1410 and the castle’s later successful defence against this same army - were extended to include a massive wall of defence with canons on half-cylinder-type bastions, a true demonstration of the Order’s power over its subjects. Moreover, Marienburg acted as a communication centre and suitable location for the accommodation for the European military nobility from all over the Continent, for its foreign princes and other West European knights taking part in the crusades against the Lithuanians.

Under Polish Rule

The Knights’ devastating defeat at the battle of Grunwald/Tannenberg in 1410, the financial burden of the First Peace of Toruń a year later, but even more the beginning of the conflict with the Estates in the Order’s territory during the Thirteen Years’ War (1454-1466), when unpaid mercenaries sold the castle to the Polish King, Kazimierz IV, in 1457, hastened the decline of the Order. Despite the ceremonial procession into the castle to assume control with the residents paying homage to the Polish king and inserting his coats of arms into the front wall and the Grand Master’s quarters becoming a palatial residence, it lost its significance as a gathering place for Europe’s nobility. On the contrary, during this new period its function was regional, as it became the seat of the governors, treasurers and economists of Royal Prussia, the centre for this governorship and official location for the regional parliament involving the various regional assemblies occasionally held in Graudenz/Grudziądz, and also for Prussian State Diet. From the 17th century onwards until the Order was disbanded in Prussia in 1780, Jesuit priests, who erected a baroque ornament depicting the Holy Mary’s miraculous powers in the castle chapel named after her, resided in the High Castle, but were forced to seek shelter elsewhere during the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). The castle, with its reputation as being impregnable since the Knights’ successful defence in 1410, gradually lost its significance as the administrative centre of Royal Prussia, while retaining its strategic importance as a fort, and as such was twice besieged and occupied by the Swedes, during the Thirty Years’ War and the Second Northern War (1655-1660/1).

Restoration with a Romantic Image – An attempt at revitalisation

Marienburg was ceded to the Prussian state following the First Partition of Poland in 1772. Only once did Frederick II (the Great) use the castle in the royal traditional manner of the Polish king: this was for the Prussian Estates to swear allegiance to him. Generally speaking, Frederick II regarded the history of this castle as being completely alien to Prussian principles, and expressly forbade his subjects to refer to the ‘unified’ West and East Prussia during the time of the Teutonic Order. As a result of this attitude, the castle was badly damaged when a parade ground was built in the summer refectory of the Middle Castle followed by storerooms in the High Castle, and slowly fell into decay when Prussian civil servants ordered the castle ramparts to be used as building materials. At the end of the 18th century, plans to demolish the castle were proposed but were then shelved because of the high cost involved.

When the equally enthusiastic Max von Schenkenburg (1783-1817) appealed passionately to save Marienburg as a memorial to Prussian history in an article in the Berlin newspaper, Der Freimühtige (= frankness, honesty), King William issued a decree in 1804 to save the building. Following a slow change in the negative attitude towards the Teutonic Order during the 18th century as a retrograde power of the Middle Ages, a different opinion emerged during the late period of the Enlightenment, helped considerably by August von Kotzebue’s play, Henry Reuss of Plauen or The Siege of Marienburg in 1805. The defeat at Grunwald/Tannenberg was obscured by placing the glorious defence of the castle under the staunch command of Heinrich of Plauen at the centre of the performance. Furthermore, this resolute commander survived a cowardly assassination attempt in the summer refectory, and this kind of theme became a traditional narrative to be copied by all the well-known German playwrights: Joseph von Eichendorff’s The last hero of Marienburg in 1830, Ernst Wichert’s Heinrich von Plauen in 1877 and Rudolph Genée’s Marienburg in 1884.

From 1815 onwards, Theodor von Schön (1773-1856), the Governor of West Prussia, supervised and pressed on with the reconstruction of the ruined Castle. As one of the future Prussian reformers, he regarded the Knights’ Order as a precursor to a constitutionally-formed Estate society, whose castle was to be claimed as a powerful symbolic identity for unity and freedom in Germany after the Napoleonic Wars. Later, King Frederik William IV of Prussia viewed the Order as a champion of monarchical rule, whose architectural symbolism – carved in stone – portrayed Marienburg as a legitimate Prussian claim to power in East Central Europe. With necessary funds in true Prussian spirit began the restoration led by the ever-present chief civil servant of the Berlin Senior Building Deputation, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. The reconstruction concentrated first on the Middle Castle and embraced a far-reaching architectural reinterpretation of this part of the building; most striking were its decorative battlements and the stained glass windows in the two refectories in the Grand Master’s Palace. The cost of these windows was met by a donation from the towns and Estates of West Prussia and were inserted by the panoramic painter, Johann Anton Breysig. The windows were to represent a link between the past and present: for example, a Prussian territorial soldier during the Napoleonic Wars was set against a Teutonic Knight. Theodor von Schön wrote the following to Schinkel: “Without the German Knights of the Order [ ... ] there would be no Copernicus, no Kant, no Herder [ ... ] and – no territorial soldier, but the blossom is more beautiful than the tree trunk (Stamm in German also means stock/tribe), and the flower is nearer to the sky than the root.” More controversial were the plans for the windows in the summer refectory, designed mainly by the artist Karl William Kolbe, to represent the sequence of great occasions affecting the history of the Teutonic Knights. It was here where Schön could assert himself vis-à-vis Schinkel who had the Crown Prince’s support; in line with the already well-known plays of glory, not the defeat at Grunwald/Tannenberg but the successful defence of Marienburg was to be portrayed in the windows, culminating in the depiction of a distinctive national and patriotic event based on the preliminary work by archivist and historian Johannes Voigt in Königsberg.

The German historian, Johannes Voigt, commenting on Marienburg in 1823:

- Indeed! Its history could of course remain silent; but this castle would testify and narrate loudly with much feeling, soul and imagination residing in the people who conquered this land and brought German culture and customs to this part of Europe.

- - Johannes Voigt. Das Ordenshaus Marienburg in Preussen (The Castle of St. Mary in Prussia), 3rd improved edition, Königsberg. P. 3.

The German writer Joseph von Eichendorff in his 1844 memorandum concerning the rebuilding of the Marienburg:

- And thus quickly and unexpectedly Marienburg reappeared when the King began to protect it from the ravages of time by rallying loyal supporters to realise this great national cause.

- - Joseph von Eichendorff. “Die Wiederherstellung des Schlosses des Deutschen Ritterordens in Marienburg” (The Reconstruction of the Castle of the Teutonic Order of Knights in Marienburg 1844). In: Die Marienburg (The Castle of St. Mary), 32 Bilder (pictures) by Joseph von Eichendorff. Königsberg, Ts / Leipzig o. J. Pp. 3-32, p. 3.32.

The historical rebuilding

A few years after the 1848 Revolution, Frederick von Quast, Prussia’s first curator, called for an archaeological and historical study of the castle as a prerequisite for an exact reconstruction of the building in its original form. This then gave impetus to the reconstruction supervised by the architect, Conrad Steinbrecht. It was preceded by yet another re-evaluation of the history of the Knights’ Order commissioned by the government. According to the outcome of this survey, Marienburg was now viewed as a bastion to protect Germany facing danger from the East. Even before the German States had united in 1871, the Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke asserted publicly and using tendentious language suggesting his country’s racial superiority vis-à-vis the Slavs that it was Prussian Germany’s national mission to bring civilisation to a Central Europe devoid of culture. This historian argued that the Polish rule of Marienburg could be seen in a wider context as representing the negative stereotype of the Poles, insinuating they were unruly, rapacious, inefficient, and dishonest. This negative interpretation of the Polish economy in contrast to the glorious German progress became more widespread after German unification and was also expressed in literary circles: for example, in Rudolph Genée’s 1884 novel, Marienburg, in which the historical continuity of the German Empire led by Prussia invoked the Teutonic Order with the castle being identified as clear proof of its task to bring German culture to the East. With this thought in mind, the rebuilding of the High and Middle Castles were nearly completed by 1923. During this period Emperor Wilhelm II also stepped in to keep up with the times and to display publicly his power as monarch, culminating in his notorious anti-Polish speech in the castle in 1902. After the death of Steinbrecht, the reconstruction continued until 1944, supervised by the last head of the German Building Department, Bernhard Schmid. However, the castle immediately became a military command post and was declared a fortress, only to become an empty shell at the beginning of 1945 after being bombarded for two months by Soviet artillery.

The German historian, Heinrich von Treitschke, commenting on Marienburg during its Polish rule:

- The Poles, distrusting the stability of the refectory pillars, filled in the spaces between them with thin walls, and the frankly simple brickwork was plastered over with lying stucco.

- - Heinrich von Treitschke. “Das deutsche Ordensland Preußen”. In: Preußische Jahrbücher, 1862. Pp. 95-151, p. 147.

The German writer, Rudolph Genée in his prologue to his novel, Marienburg (1884).

- A memorial forever

- In the new fatherland

- You stand as a German observation point

- Facing the East

- - Rudolph Genée. Marienburg. An historical novel. Berlin, 1884. P. vii.

The Polish Perception

In Polish literary writing, historiography and art, the Polish-Lithuanian victory of 1410 is recorded as a paragon of masterly narration to serve as a national moral lesson on how to resist foreign rule following the Second Partition of Poland. Parallel to the German tradition of historiography, a link was also shown between the Teutonic Order, the Prussian State and the German Empire to prove the persistent German Drang nach Osten. During the period of Polish Romanticism, it was the writer Juliusz Słowacki (1809-1849) who portrayed the Teutonic Order as being driven by a very sinister religious fanaticism and exaggerated secular claim to power, becoming the model for stereotyping the crusaders (Krzyżak). Even when Adam Mickiewicz, probably the most well-known Polish poet of the 19th century, in his 1828 political play Konrad Wallenrod, a few years before the November Polish Uprising in 1830/31, focused primarily on Russian rule and the Marienburg continued to act as a symbol of repression and constraint. As the drive to Germanise the Prussian part of divided Poland during the second half of the 19th century increased, the Teutonic Order was also interpreted as an early incarnation of the German Drang nach Osten by the Polish historian Karol Szajnocha in his comprehensive work, Jadwiga i Jagielło (1855/6).

Following the January Uprising in 1863/4, the myth of Grunwald as a powerful image grew in strength; an analogous demonstration to the present day – the defeat of a seemingly almighty opponent. This idea was later reinforced by Jan Matejko’s highly popular painting, Bitwa pod Grunwaldem (1875-1878). However, the most controversial use of the Grunwald motif in literature was later, in the 1900 novel Krzyżacy (Knights of the Cross) by the Nobel Prize Winner, Henryk Sienkiewicz, who ended his book with a lavish description of the degenerate crusaders’ defeat and their just punishment at the battle of Grunwald/Tannenberg. Together, Sienkiewicz’s highly successful novel and Matejko’s painting of this battle continued to keep this memory alive, most vividly celebrated 500 years later with a film of this victory in 1410 directed by the Communist Aleksander Ford (1908-1980).

The Polish writer, Henry Sienkiewicz in his 1900 novel Krzyżacy:

- Just looking at the Castle of Mary must fill Polish hearts with fright: this fortress with its High and Middle Castles and bailey can in no way be compared to any other castle in the world.

- - Henryk Sienkiewcz. Krzyżacy [1900]. T. 2. Warszawa, 1955. P. 377. Translated by Christoph Garstka as: “Das Kreuz mit den Rittern. Die Darstellung der Ordensritter in der polnischen Literatur des 19. Jahrhunderts”. In: Die Marienburg. Vom Machtzentrum des Deutschen Ordens zum mitteleuropäischen Erinnerungsort. Ed. by Bernd Ulrich Hucker, Eugen Kotte, Christine Vogel. Paderborn, Munich, Vienna, Zürich, 2013. Pp. 173-186, p. 173.

The Reconstruction of the Castle after World War II

In 1945, about 50% of bricks had been destroyed, not a single room was left standing and only the castle’s foundations were visible. The decision to rebuild was delayed due to various ideas about its future first being discussed because the castle was still being interpreted as a victory over Poland’s archenemy and as a war trophy to be kept. After a dreadful fire in the Middle Castle, the systematic rebuilding began and continued in earnest supervised by the newly-formed castle museum (Muzeum Zamkowe w Malborku, still in existence today) so that by 1973 the High and Middle Castles were all but finished, but not the castle church. After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, the lower room of worship in the High Castle, the Chapel of St Anne, was rebuilt, and the karwan and the eastern defence walls were completed during the following years, resulting in Marienburg being declared a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1997.

The Polish press during the postwar era (1948)

- Marienburg is the symbol of our struggle on Polish soul, it is the ever-changing symbol of the power of the Knights’ Order in Gothic form, its cruelty and arrogance but also its downfall and defeat.

- - Stanisław Antoni Michalowski: “Śmierć zamku”. In: Odra 12/13, 1948. P. 2, translated by Tomasz Torbus. “Marienburg as seen in the Polish Press 1945-1973 – the reconstruction and the “domestication’ of a foreign heritage”. In: Marienburg from being a Centre of Power to becoming a Place of Memory in Central Europe. Ed. by Bernd Ulrich Hucker, Eugen Kotte, Christine Vogel. Paderborn, Munich, Vienna, Zürich, 2013. Pp. 207-221, p. 210.

Its significance and use today

During the 1970s, Eleonora Zbierska suggested that Marienburg no longer be remembered as a being once a place of conflict but as a place where the people of Europe can converge and converse. The Muzeum Zamkowe w Malborku did its best to link this demand for change by conceiving the idea of education in an interesting way with historical documents, detailed exhibitions and spectacular historical dramas (for example, since 2000 the annual open-air The Siege of Marienburg) and other impressive artistic productions (for example, the Magic of Marienburg in lights). These historical exhibitions documenting the history of the castle concentrated on four main themes: reconstructing the castle on the site as it once was, the castle as a place of residence and business, its military and political function when it was ruled by the Teutonic Knights and then by Poles and finally the castle as a religious and cultural centre in the region. In addition, Marienburg was also inter alia a meeting place for Europe’s youth with its museum, exhibitions and also a library with mainly non-fictional works, an art studio, a conversion workshop, its own publishing facilities, a centre for European co-operation and finally since 1976 housing the State Archives of Elbing/Elbgląg, truly a place of learning. Thus, the castle is much more than just a tourist attraction: it is a place of remembrance, a museum and a cultural centre where people meet and come together, so relevant to our Europe of today.

The Polish curator, Eleonora Zbierska in 1973 expressing her thoughts with the completion of the rebuilding of the High and Middle Castles in sight:

- Marienburg, a singular expression of German-Polish relations, continues to arouse so much controversy and interpretation [ ... ]. It seems that with the present situation in Europe we now have the unique chance to stimulate young minds, making them look objectively at history and not to be corrupted by myths and nationalistic arguments.

- - Eleonora Zbierska. “Perspektywy dla Malborka”. In: Polska 6, 1973. Pp. 42-43, p. 43.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- How has the symbolism of the castle of Marienburg changed over different periods? What political events influenced these changes?

- Is there a building whose use and symbolism has changed in your city/country? What brought about these changes?

- Is there a building that has been destroyed for its symbolism in your city/country? Do you approve or would have solved the situation differently?

Further reading

- Hartmut Broockmann. Die Marienburg im 19. Jahrhundert (Marienburg Castle in the 19th century). Frankfurt a. Main, Berlin, Propyläen Publishing Co., 1982.

- Die Marienburg: Vom Machtzentrum des Deutschen Ordens zum mitteleuropäischen Erinnerungsort (Marienburg Castle: From the centre of power of the Teutonic Order towards Central European site of memory). Ed. by Bernd Ulrich Hucker, Eugen Kotte et al. Paderborn, Munich et al., Ferdinand Schöningh, 2013.

- Mariusz Mierzwiński. Die Marienburg (Marienburg Castle). Warszawa, United Publishers Ltd, 1993.