1.10 Margaret, Jadwiga, and Unions

Anders Fröjmark, Anne Brædder, Giedrius Janauskas, Małgorzata Dąbrowska

Like in most countries in the world, the countries in the Baltic Sea region have been ruled by many kings throughout history. But a few women have also been in power and left their mark on how international politics developed in the region. In the 14th century, two queens in different parts of the Baltic Sea region had the power to carry out their similar visions about unifying different areas in the Baltic Sea region.

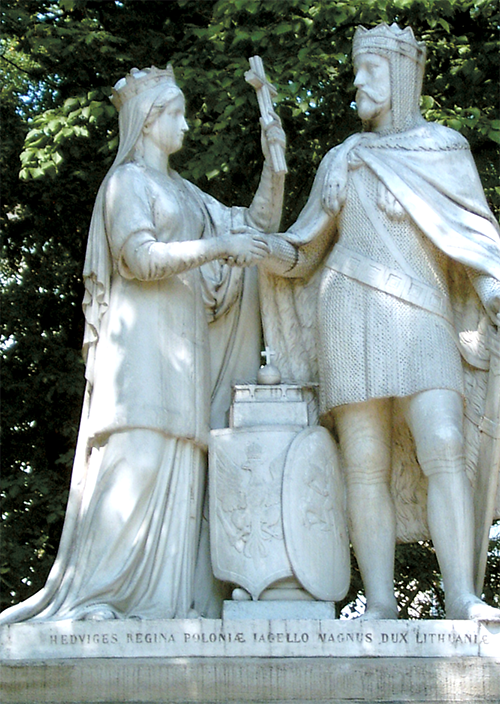

This is the story of Jadwiga of Poland who initiated the “composite monarchy” of Poland and Lithuania in 1386 and of Margaret I who unified Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 1397. The union of Denmark, Norway and Sweden lasted until 1523 and Jadwiga’s marriage to Jogaila (Christian name Władysław Jagiełło) from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania initiated the process of the creation and development of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which lasted until its partitions in the late eighteenth century.

Jadwiga and the relationship of Poland and Lithuania

Jadwiga/Hedwig de Anjou (1374–1399) was the youngest daughter of Louis I/Louis the Great, King of Hungary, Croatia and Poland and his wife Elizabeth of Bosnia. In 1375, her father Louis the Great had reached the agreement with Duke Leopold III of Austria about Jadwiga’s marriage to William of Austria, the son of Leopold III. Imagination of Jadwiga’s father has been related to the future of the Kingdom of Hungary. However, after the death of Louis in 1382, Jadwiga’s elder sister Mary was crowned "King of Hungary".

The Polish nobility were so strongly in favour of having the king settle in Poland that Queen Elizabeth of Bosnia could not convince Polish aristocracy to change their position. Queen Elizabeth took the decision to announce that Jadwiga might become King of Poland, but at that time Jadwiga still lived in Hungary. After protracted discussions with the Polish nobility, Jadwiga was sent to Poland; however, the Polish nobility refused to accept her intended husband William of Austria. In 1384, she became the first female monarch of the Kingdom of Poland. According to Polish and Lithuanian scholar consensus, Jadwiga was crowned “king”. Historian Oscar Halecki reminds, with the 15th century chronicler Jan Długosz as his source, that William went to Kraków in the first half of August in 1385, but was barred entry to Wawel Castle. Finally, it was announced that the agreement of engagement with William of Austria was cancelled, and William was forced to leave Poland.

The Act of Krėva/Krewo was signed in the same year. The Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jogaila, had convinced Polish Lords and Queen Elizabeth that he would be the best candidate. He would convert to Catholicism, marry Jadwiga, and assume the throne as King of Poland, creating a “composed monarchy” consisting of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which in 1387 was converted to Christianity. Jogaila had to pay 200,000 florins to William in compensation.

According to historian Jūratė Kiaupienė, in Polish historiography, the marriage act, known as the Act of Krėva/Krewo, was interpreted as signifying a union which incorporated Lithuania into Poland. In recent Lithuanian analysis, however, the Act of Krėva/Krewo is viewed as the ratification of a marriage contract rather than an international treaty constituting a union, although the Latin word applicare used in the Act of Krėva/Krewo is still discussed by historians and has no exact translation or explanation. In fact, it proved impossible to integrate the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Polish state at this time, and this fact was later recognised in 1392 when Jogaila’s cousin, Vytautas, was made Grand Duke of Lithuania under the formal overlordship of Jogaila.

In 1386, Władysław Jagiełło (Jogaila) married Jadwiga in Kraków. This marriage on the basis of personal union marked the beginning of dynastic ties between Poland and Lithuania. Placing the dynastic union of Jogaila and Jadwiga into a European context, Lithuanian authors use the term “composite monarchy” – the joining of two autonomous states under the same ruler, however, Polish researchers say that the marriage enabled the union of Poland and Lithuania, establishing a large and powerful state in East Central Europe. After she married Władysław/Jogaila, she still maintained the status of “king” and added new titles she gained from her husband. She did not lose her prerogatives after marriage. For example, she received a tribute from Peter I (Moldavian hospodar) and a year later negotiated with the Teutonic Order for the return the Land of Dobrzyń.

Jadwiga was well-educated and prepared to rule the country. She was by far the most powerful woman in Central Europe in medieval times and one of the greatest rulers in history of Poland. She married the much older Władysław/Jogaila for the purpose of strengthening the Kingdom of Poland’s political/religious power in East Central Europe. Jadwiga also looked for consensus and peaceful cooperation with the Teutonic Order. Her politics helped to prepare the Polish and Lithuanian armies for the Tannenberg/Grunwald/Žalgiris battle against the Teutonic Order, the largest battle in the medieval history of both countries. As an educated, diplomatic, devoted woman, she actively supported the Catholic Church, took care of the Kraków Cathedral, and monasteries, and brought together the elite of Polish intellectuals of that time. In fact, Jadwiga together with Władysław/Jogaila also implemented educational reforms, re-established the Jagiellonian University (closed after the death of its founder Kazimierz the Great – Jadwiga's uncle), established the Faculty of Theology, and also established the Lithuanian College at the University of Prague. New schools, hospitals and churches were created during her reign.

On 22nd of June 1399, her daughter Elizabeth Bonifacia was born. Just three weeks later, both mother and child died and both were buried in Wawel Cathedral in Kraków. In her last will, she left her entire personal fortune to the Jagiellonian University, which helped to reestablish it in 1400. According to tradition, the sceptre was founded by Jadwiga and is the oldest known rector's insignia in Poland and one of the symbols of the Jagiellonian University.

Memory of Jadwiga in Poland and Lithuania

Since the 15th century there has been a broad cult of Jadwiga in Poland. First attempts to canonise her began soon after her death as did pilgrimages to her grave. She is a patron of Poland as a whole and also of several cities. In 1997, Pope John Paul II canonised Jadwiga. The Pope appreciated St Jadwiga's merits in promoting religious and cultural cooperation between the peoples of Europe. The daughter of King Louis I, the King of Hungary and Poland, as Queen of Poland and wife of the Grand Duke of Lithuania Jogaila, she sought to have Lithuania baptised and to settle disputes with Hungary. Queen Jadwiga taught her people to exercise freedom in the spirit of love and truth, cared for the poor, the sick, the orphans, and the widows. She actively participated in the political life of that period and was able to combine Christian principles with the interests of the state.

Jadwiga also helped spread Christian values in other European countries. The Roman Catholic Church regards her as the patron of the queens and united Europe. Consequently, in Poland Jadwiga is well-known in her own right, whilst in Lithuania she is mainly known as Jogaila’s wife. As Jadwiga contributed much to the liturgical supplies and books of the Vilnius Cathedral and other early Lithuanian churches, creating conditions for the spread of Catholic and literary culture in Lithuania, she is also called the Lithuanian Apostle.

The most famous vestige of Jadwiga in Poland is the Rationale of Saint Jadwiga, a part of the bishop’s liturgical wearing, which is still in use (only for special mass) at Kraców Cathedral and was handmade by Jadwiga. She is also responsible for one of the greatest medieval works of art in the Polish language, the Psalterium trilingue, the oldest known Polish translation of the Book of Psalms, written for her according to one tradition. The figure of Jadwiga was present on Polish banknotes after World War I and the project of a new banknote with Jadwiga has been planned, but not yet realised.

Margaret and the union of Denmark, Norway and Sweden

Margaret I (1353–1412) was daughter of Valdemar IV of Denmark and Helvig of Schleswig. In 1363, when Margaret was 10 years old, she married Haakon VI of Norway. In her marriage, she gained the title of queen of two kingdoms, since Haakan was for a short period of time also the king of Sweden. Their son Olaf was born in 1370. Margaret was by far the most powerful woman in Northern Europe in medieval times.

Margaret’s influence on international politics especially in the area of Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Germany began when her father Valdemar IV died in 1375. At that time, she was the only living child of Valdemar IV and it seems that he had chosen her son as his successor although he earlier had pointed to his older daughter’s son Albert IV, Duke of Mecklenburg, to be his successor. However, Denmark being an elective monarchy, the final choice was up to the magnates.

At the time when her father died, Margaret was based in Akershus in Norway owing to her marriage to the Norwegian king Haakon. But when Valdemar IV died, she went to Denmark with her five-year-old son Olaf, who was elected king in 1376. As Olaf was only a young child, a regency consisting of his parents Margaret and Haakon and the Royal Council was inaugurated. Only four years after this, Haakon died, which made the now 10-year-old Olaf king of both Denmark and Norway. As regent, Margaret governed both kingdoms, with the authority to handle their foreign policy. The two united kingdoms constituted a strong power in Northern Europe. Olaf died in 1387 at the age of 17 and therefore a new heir for Margaret had to be found.

In a unique series of events, Margaret was hailed as regent of both Denmark and Norway. She was to hold this position in her own right, and not as the king’s mother as before. She would govern the kingdoms until she and they had agreed upon a new king. The Norwegian constitution made it natural for her to establish the new kingship there first. In 1389, she had her adoptive son Eric recognised as king of Norway. Eric is often referred to as Eric of Pomerania.

Meanwhile, in Sweden, Haakon VI and his father Magnus had been deposed from the Swedish throne in 1364. Instead, a nephew of King Magnus, Albert III of Mecklenburg, had been elected. However, King Albert’s use of German knights in key positions in the kingdom alienated large parts of the Swedish aristocracy and clergy, and representatives of those entered into contact with Queen Margaret, who held some territories in Western Sweden after her deceased husband.

With the help of Queen Margaret, King Albert was deposed in Sweden. It took some years in order to have the new situation internationally recognised, and also to establish the legal foundations for what would be a union kingdom, but in 1396, young Eric was elected king in Denmark as well as in Sweden. The following year saw a large meeting of Scandinavian prelates and magnates in the Swedish coastal city of Kalmar, where Eric, aged 15, was crowned as Union King of the three kingdoms.

In fact, Queen Margaret held the reins of the three kingdoms until her death in 1412. She ruled a large area of sea and land stretching from Greenland in the west to Karelia on the border to Russia in the east. Her ability to set up long-term goals for her actions and pursue those with relentless resolution inspired awe and admiration in friends and enemies alike. She could be merciless to those who stood against her, but her rule is an indisputable success in most respects, and it should be remembered as – for the most part – a period of peace and increasing – if heavily taxed – prosperity, which was far from the rule in contemporary Europe, ridden by plague and endemic conflict.

The Kalmar Union survived its founder and lasted until Sweden finally broke away from the union in 1523. Today, five countries share the succession of the three united kingdoms. Each of them has its own historiography concerning the union period. Some examples of Danish and Swedish popular historiography concerning Queen Margaret and the Kalmar Union are presented below.

In order to explain the decisive way in which Queen Margaret carried out her plans, there are some notions we should bear in mind. First, she was the daughter of a very successful and visionary king, Valdemar IV, who restored and reunified the Danish kingdom which in the 1330s had virtually ceased to exist. He had also dreamt of gathering Norway, Denmark and Sweden in one union, and she continued to pursue this goal. Secondly, through her marriage to Haakon VI, she became queen of two kingdoms, Norway and Sweden. Even though Sweden was lost to Haakon after only one year, Margaret was raised and educated as the true queen of Sweden, and never gave up her title and her claims.

Memory of Margaret in Denmark

In Denmark, Margaret I is well known in a present context. The queen of Denmark today is called Margaret II (1972–) so the name alone reminds Danes that there had been a queen with the name Margaret in the past. These two Margarets are the only female sovereigns of Denmark since Gorm the Old ruled Denmark in the middle of the 900s.

The memory of Margaret I is present in other ways than by sharing the same name as the present queen. The notion of her as the one who “gathered the North”, as it is often said, is strong. This can be seen if you look at the mandatory list of topics that Danish students must be taught in public schools. The list comprises 29 historical topics from lifestyle in Stone Age to the act of terrorism in New York September 11, 2001. The establishment of the union of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 1397 is a part of this list. There are at least two memorial stones for Margaret I and two statues in different places in Denmark. She is buried in Roskilde cathedral where several other Danish kings and queens are buried. Margaret I also plays an important role in a new entertaining history project for young children that consists of a two-volume book, a board game, a tablet game, a TV series and a music album about the history of Denmark. In the board game about Denmark’s national history, children can be the character of Margaret I. They can read about the union of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in the book and one of the tasks in the tablet game is also about Margaret I. The project is called “Sigurds Danmarkshistorie”.

Memory of Margaret in Sweden

The Swedish historiography of Queen Margaret presents a mixed picture. At the time of her death, she was portrayed as a cunning but successful woman. In the early modern period, when there were frequent conflicts between Denmark and Sweden, and in later historiography, there has been a tendency to underline her Danish background, in spite of her being both Norwegian and also Swedish queen from the age of ten, and also educated as such. She has been portrayed as something of a Danish imperialist, who in spite of the idea of the union, appointed foreigners as bailiffs and captains in Sweden.

In recent days, a more positive picture may be discerned. She is portrayed as a great leader and visionary, the creator of the Nordic Union. In a number of children’s books she has become something of a role model for Swedish girls.

In 1997, the 600th anniversary of the Kalmar Union was much celebrated in Sweden, and particularly in Kalmar. Heads of state of the now five Nordic countries met in Kalmar. A popular TV series for children (Salve) was aired, with King Eric as one of its heroes. The anniversary was also marked by theatre plays and conferences. Historian Michael Linton’s thorough study of Queen Margaret from 1971 was republished in a more accessible edition.

In Swedish schools, one may notice a mixed picture. Elementary schools give a rather neutral picture of the union as part of Swedish history. In high school however, it is rather used as a background for the actions of Gustavus Vasa, who is also traditionally seen as a liberator and a nation builder.

Sagan om Grållen by Bertil Almqvist (1959), is an illustrated and humorous book on Swedish history, in which Sweden is depicted as a horse, and the rulers as riders. The actions of Queen Margaret are seen in the context of foreign dominance in Sweden, a dominance that is always brought about by the magnates, who depose every ruler who is not to their liking. Margaret herself is portrayed as – perhaps – not so bad, but the rule of her foster-son Eric brought misery to Sweden.

- The magnates […] now (1371) imported a German exercise master, Albert of Mecklenburg, to discipline me, poor Swedish farming horse!

- But – häst [=horse] hast Du mir gesehen! [have you seen me?]

- Suddenly I had a beautiful and authoritative Danish woman on my back!

- The magnates had made a miscalculation about Albert. As soon as he had gotten into the saddle, he went all in to make Sweden a German colony, and began putting German princes at Swedish manors. In their distress, the magnates asked Margaret, Queen of Denmark and Norway, to be so kind as to come and rule over Sweden, that is me, as well!

- In Kalmar in 1397 (the ‘Kalmar Union’) she gave all three crowns to her foster-son Eric of Pomerania. I was now degraded to be a draught animal for taxes, and had the doubtful pleasure to pull to Copenhagen the taxes, which the bailiffs of the king (the worst of them was a man called Jösse Eriksson) had beaten out of the poor Swedish peasants. You must know that Eric of P. was continuously in war against the threatening German overlordship over the Nordic countries, and that was very expensive.

- - Bertil Almqvist 1959, Sagan om Grållen. 1859, unpaginated.

Dag Sebastian Ahlander, Margareta: Drottningen som visste vad hon ville (Margaret: The Queen Who Knew What She Wanted), 2002, is a children’s book written by a Swedish diplomat.

- Epilogue

- It has been a particular pleasure to write this book about Margaret, the Queen of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. In Sweden, we have had a deplorable tendency to erase her from our history. This is why I wanted to create attention to this remarkable woman’s destiny.

- We have listened more to Karl Knutsson Bonde’s and Gustavus Vasa’s opinions of the union, but in their days, the Union Kings were Christopher of Bavaria and Christian the Tyrant. Still, Margaret brought about what many in the North had dreamt of throughout history, to accomplish law and order in a united North. The first thirty years was a peaceful and happy period for the three Nordic Kingdoms.

- For these reasons, Margaret is a great European – and a great Swede. Even if she was born as a Danish Princess, she grew up in the care of Saint Birgitta’s daughter Märta, and she wrote in Swedish as her mother tongue. She became Queen of Sweden when she married King Håkan in 1363. In 1388, the Swedes elected her as Sweden’s Lady and rightful Master, and she ruled Sweden until her death in 1412.

- - Dag Sebastian Ahlander. Margareta: Drottningen som visste vad hon ville. 2002. P. 103.

Boken om historia 1 (Stina Andersson and Elisabeth Ivansson, 2007) is a textbook for Swedish elementary schools.

Under the heading “Margaret – A Powerful Queen”, Margaret is portrayed. It is said that she was born in Denmark, and that her father, when she was nine, decided that she should be married to the “King of Norway”. After the death of her father, her husband, and her son, the people and magnates of the two kingdoms elected her to be regent. Meanwhile, in Sweden, the magnates had elected Albert of Mecklenburg, but regretted their choice. They wanted Margaret to liberate them. Albert, however, derided her, and nicknamed her “King Breechless” (or “Trouserless”). She should stay at home as other women did, and not make a spectacle of herself by going to war. She however was victorious, and became Queen of all the North, a mighty realm, stretching from Finland, then belonging to Sweden, to Iceland, then belonging to Denmark (wrong for Norway).

She created the Kalmar Union, and a document with rules for the Union was signed in Kalmar, where her adoptive son Eric, a Swedish name chosen to please the Swedes, was crowned.

She continued to rule in spite of Eric having been crowned. She wanted to be a just queen, and ordered that even the knights and the rich should pay taxes, and not only the peasants. She did not care that many were upset, and chose collaborators who thought as she did.

After her death, Eric reigned. But the Swedes did not like him, since he wanted to govern Swedish peasants with bailiffs from Denmark and Pomerania, who had a different way of treating peasants than what the Swedish farmers were accustomed to. He was called Eric of Pomerania since he was regarded as a Pomeranian, not a Swede. On page 157, she is named among “Famous Swedes in the Middle Ages”.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Compare the two queens – what do they have in common? What sets them apart?

- Compare how the queens are seen today in different countries? Why – is it politics? How does the fact that they are female influence the view (if at all)?

Further reading

- Anders Bøgh. 2012. Margrete 1., 1353–1412. https://danmarkshistorien.dk/leksikon-og-kilder/vis/materiale/margrethe-1-1353-1412/ (visited November 22, 2018).

- Norman Davies. God's Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I: The Origins to 1795 (Revised Edition). New York City, Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Vivian Etting. Queen Margrete I, 1353–1412, and the Founding of the Nordic Union. Leiden, Brill, 2004.

- Robert I Frost. The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Volume I: The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union, 1385–1567. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Oscar Halecki. Jadwiga of Anjou and the Rise of East Central Europe. Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America, 1991.

- Zigmantas Kiaupa. The history of Lithuania. Vilnius, Baltos lankos, 2002.

- Andrzej Rachuba, Jūratė Kiaupienė and Zigmantas Kiaupa. Historia Litwy: Dwugłos polsko-litewski (History of Lithuania: A Polish-Lithuanian dialogue). Warszawa, DiG, 2008.

- Liv Thomsen. Historiens heltinder (Heroines of History). København, Gyldendal, 2014.

- Michał Tymowski. Une histoire de la Pologne (A history of Poland). Montricher, Les Éditions Noir sur Blanc, 1993.