1.12 Reformation

Anders Fröjmark, Juhan Kreem and Vitalija Kasperavičiūtė

In 2017, the five-hundred-year anniversary of the Reformation was commemorated in countries around the Baltic Sea, however in different ways, and with different degrees of intensity. For example, in Denmark, few people may have failed to notice the stream of books, expositions, and attention in the media, while in neighbouring Sweden, celebrations were more or less invisible to the general public. On the other hand, the Pope was invited to participate in the commemoration, which was anything but self-evident in a celebration of an event that once led to a schism within Western Christianity.

In Lithuania, the Seimas decided to declare the year 2017 to be the Year of the Reformation. The Parliament’s decision was adopted owing to the fact that many Christian countries would celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation and commemorate the year 1517, when Martin Luther announced his theses. The resolution of the Seimas highlighted the fact that the Reformation produced many prominent personalities in Lithuania who cherished and promoted the love for the native language, were active in the field of writing and culture, and shaped the education system. They include Martynas Mažvydas (Martinus Mosvidius), Kristijonas Donelaitis (Christian Donalitius), Jonas Bretkūnas (Johannes Bretke, Bretkius) and Abraomas Kulvietis (Abramus Culvensis). In addition, the Reformation prompted new social, economic, political and cultural processes in Europe, which also had a profound impact on Lithuania.

In Estonia, the traditions of Lutheranism have always been strong. In the general perception, the Lutheran church did a lot to foster the development of Estonian language and school education. 2017 was celebrated most of all by the Estonian Lutheran Church, which connected the celebrations with the centenary of the Estonian Republic in 2018. Also in 1924, when the jubilee of the arrival of the Reformation to Estonia was celebrated, the clergy stressed that it was Luther who spoke about freedom and thus stimulated Estonians to ultimately gain personal and political freedom. The position of Lutheranism in Estonian history is, however, not that straightforward. Although many leaders of the Estonian national movement were Lutheran pastors, the church organisation itself was part of the ancien régime, and for example the conversions to Russian Orthodoxy in the 19th century indicate that Lutheran church could not cover the spiritual needs of the people.

The Events

The Reformation is usually considered to have begun with the publication of the Ninety-five Theses on the Power of Indulgence by Martin Luther in 1517. There was no definite schism between the Catholics and the nascent Lutheran branch until the 1521 Edict of Worms, where Luther was outlawed, but tensions had grown during these years, and the position of Luther and his entourage gradually became more radical.

Luther had begun by criticising the sale of indulgences and some aspects of the teaching of Purgatory and the Treasury of Merit. The Reformation developed further to include a distinction between Law and Gospel, a complete reliance on Scripture as the only source of proper doctrine and the belief that faith in Jesus is the only way to receive God's pardon for sin rather than good works.

In the Baltic Sea region, early adoption of Reformation thinking was predominantly an urban phenomenon, while people living in rural areas were generally satisfied with following the recurrent cycles of the Christian year, attending to the sacred rites, and having the parish priest as their mediator between heaven and earth. In towns, literacy was widespread, and there was an openness to new ideas. The fifteenth century had been a time of growing urban centres in northwestern Europe. Cites were places of intense religious fervour and new religious movements, more or less integrated in the Catholic hierarchical structure of surveillance and guidance. In the following century, the Reformation found the towns ripe for change. In Riga the preaching of the Reformation started as early as 1522, soon after that, the first preachers in Tallinn recorded. In the then-Danish coastal town of Malmö, Reformation ideas took hold in 1527.

This movement coincided with changes on the political level: the birth of the Early Modern Princely State. Princes like Henry VIII in England, Christian III in Denmark and Norway, and Gustavus Vasa in Sweden were not the first to strive for a more direct control over their territories and the resources of the same, including those belonging to churches and abbeys, which were exempt from taxes, but they proceeded with a greater self-confidence than their predecessors, partly boosted by a Reformation ideology which also criticised Church property and the religious hierarchy.

At the same time, the authority of the papacy and the central institutions of the Church had suffered damage due to the Great Schism at the end of the 14th century and the ensuing Conciliar Movement. The impression among Catholic believers across Europe was, that left to itself, the Catholic hierarchy would easily fall victim to fractional battles and corruption, and only firm guidance from the Emperor and other worldly princes had succeeded in steering the Church back on course. The crucial loss for the Catholic leadership was perhaps not so much a loss of autonomy as of moral authority – and this in a religious climate marked by strong spiritual movements among laypeople.

In some places, the Reformation movement was radical and accompanied by bouts of iconoclasm, in which churches were violently cleansed of images and objects belonging to the Catholic rite, and mendicant friars were chased from their convents. Not surprisingly, such scenes took place almost exclusively in urban settings, where the Reformation was carried by a real popular movement. In agrarian parts of the Baltic Sea region, such incidents were rare. Instead it was the attitude of the rulers that determined which path events would take.

An example is the Swedish King, Gustavus Vasa (1523–1560), who saw the need to tread carefully in order not to stir up resistance in a country that was deeply anchored in the Catholic faith, and where the cult of saints was more productive in the Late Middle Ages than almost anywhere else in Christendom. The goal of Gustavus was to strengthen the finances of the realm by nationalising Church property. This meant that most abbeys and convents were closed, but over a number of years and with as little vexation as possible. While the office of Bishop was suppressed in Denmark, Gustavus kept it in place, but stripped it of financial resources. The implementation of the Reformation continued throughout the 16th century. At a synod in Uppsala 1593, it was finally decided that the Church of Sweden should adhere to the Evangelical, that is Lutheran faith. Two years later, Vadstena Abbey was closed. A rebellion in 1598, led by Duke Charles, the youngest son of Gustavus, deposed King Sigismund with the argument that a Protestant nation could not have a Catholic monarch. This was, hopefully, the last civil war in Sweden, but since Sigismund was also King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, it was the beginning of the disastrous wars between Poland and Sweden in the 17th century.

While the Lutheran branch of the Reformation was successful in the most of the Baltic Sea region, there were also occurrences of the Reformed (Calvinist) variant, especially in Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, where the reign of Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572) was marked by religious tolerance. Multiculturalism and multiconfessionalism are sometimes considered to be Poland’s greatest contribution to European culture. With ten different confessions, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had no peer in this respect in the 16th century, even in comparison with such diverse countries as Poland and Transylvania. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania stood out in the Central and Eastern European region for the rapidity with which it gave legal sanction to multiconfessionalism. The boundaries of tolerance later narrowed in both Poland and Lithuania, but changes took place slowly and without compulsion, and multiconfessionalism survived up to the 20th century. The case can be made that 16th century Lithuania was the birthplace of European tolerance.

Notably, some families within the high nobility converted to the Reformed faith. Among them were branches of the powerful and influential Lithuanian Radziwiłł family. They chose Calvinism because it was better suited for their plans to weaken the Grand Duke’s power, which was in large part based on the authority of the Church, and they wished to lessen the influence of the Catholic Church in general. In Prussia, the Lutheran faith was widespread, but most of Sigismund’s Polish and Lithuanian subjects remained Catholics.

Leaders within the Roman Catholic Church responded with a Catholic Reformation, often termed the Counter-Reformation. Northwestern Europe, except for most of Ireland, came under the influence of Protestantism. Southern Europe remained predominantly Catholic apart from the much-persecuted Waldensians. Central Europe was the site of much of the Thirty Years' War and there were continued expulsions of Protestants in central Europe up to the 19th century. Following World War II, the removal of ethnic Germans to either East Germany or Siberia reduced Protestantism in the Warsaw Pact countries, although some members of the faith remain today. Absence of Protestants, however, does not necessarily imply a failure of the Reformation.

The Jesuit Order was founded in 1534 to foster a Catholic revival and counteract the influence of the Lutherans and other Reformers. Its main methods were education and overseas missions. In 1579, it founded Vilnius University.

The end of the Reformation era is disputed: it could be considered to end with the enactment of the confessions of faith which began the Age of Orthodoxy. Other suggested ending years relate to the Counter-Reformation, the Peace of Westphalia (1648).

Effects of the Reformation – in the Baltic Sea Region and beyond

The effects of the Protestant and Catholic Reformations were profound. One of the most important effects in the long run was a rise in the general level of education. Martin Luther insisted that there was a general priesthood of all baptised Christians, which meant that everyone – women and men alike – had a personal responsibility in spiritual matters, and should therefore be able to read the Bible and the Catechism. But also in the Catholic world, education was used as a means of elevating Catholic consciousness. New educational orders were founded such as the Ursulines and the Jesuits, and the long-term effects were the same as in the Protestant world.

Book-printing in national languages was also fostered by the religious conflicts. Catholics and Protestants both poured out catechisms and other religious books. To give just a few examples: In Finland, then the eastern part of the Kingdom of Sweden, Mikael Agricola (c. 1510–1557) developed the standard for written Finnish with his Abckiria in 1543, and published a Finnish translation of the New Testament in 1548. Meanwhile, in Königsberg, Martynas Mažvydas (c. 1510–1563), published the first printed book in Lithuanian, a catechism including a primer, in 1547.

New universities were founded in the aftermath of the Reformation, such as Königsberg (1544), Vilnius (1579), and Tartu (1632).

On the negative side, Europe experienced a loss of a sense of community. Catholic faith and Catholic liturgy had been uniting elements, from Tromsø in the north to Syracuse in the south, from Vilnius in the east to Santiago de Compostela in the west. Now members of different religious denominations ended up waging war against each other. Seventeenth century Europe, in particular, was tormented by wars, which were at least partly motivated by religion.

In the Baltic Sea region, the Reformation had greater consequences than in most parts of Europe. The political environment underwent long-lasting changes, for example, the submission of Norway to the Danish Kingdom in 1537 after the forced dissolution of the Norwegian Church Province – the strongest political and ideological organising force in Norway of the late medieval era, whose leader was the Catholic Archbishop of Nidaros (Trondheim). Another example is the crisis and dissolution of the medieval Livonia, where the raison d’être of the Teutonic Order and Catholic Bishops with extensive secular power was undermined. Members of the Order, including the last Master, Gotthard Kettler, converted to Lutheranism. The lands of this weakened medieval principality were subsequently fought over by Poland, Lithuania, Denmark, Sweden, and Russia.

South of Livonia, the 1569 Union of Lublin created a single state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, also known as the Rzeczpospolita. This geopolitical situation created a strong Catholic state. Because of this, the Catholic Reformation was quite successful in Lithuania and Poland.

While the Catholic Church had fought fiercely for its independence throughout the Middle Ages, the Reformed movements sought protection and support from worldly rulers, and ended up more often than not being State Churches. This may in the long run have contributed to a weakening of their resilience in times of political oppression and/or occupation. Note as a contrast the role of the Catholic Church in Lithuania and Poland during Soviet occupation and communist rule.

A noteworthy aspect of the Reformation in the north is its effects on ethnic minorities, such as the Sami. At the end of the Middle Ages, the Sami typically were baptised, had Christian names, and practiced fasting on Fridays. The reformers, however, regarded them as pagans and despised their fasting as vain efforts at justification by works. Thus, the Sami were subject to a second “Christianisation”.

While the world of western Christendom was torn asunder by discussions, and even battles, over the right way to follow Christ, the Eastern Orthodox Churches were seemingly less affected. The liturgy and teachings of the Orthodox Church apparently remained stable. However, Orthodox bishops in the wide territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, perhaps more for political than for religious reasons, negotiated with the Papacy in Rome to form a union, without giving up the characteristic traits of Orthodox religious life and liturgy. The result was the Union of Brest in 1595, which resulted in the so-called Ruthenian, or Uniate, Church – a church with Eastern rite under the obedience of the Roman Pontiff. Such churches still form a part of the religious landscape of eastern and central Europe.

In the countries where the Reformation prevailed, the Catholic churches were relatively easily reconverted to serve Lutheran congregations. Often, old altarpieces and images of saints were kept, or moved to less visible places. In other cases, the changes were more comprehensive.

St Peter’s Church in Malmö is a Gothic, 14th century church that for generations served the Catholic congregation in this prosperous coastal town. Malmö proved to be a fertile ground for Reformation thought, and the Malmö Reformation carried with it bouts of iconoclasm that were otherwise unusual in the Nordic countries. Many altars and images of saints were destroyed in 1529, and in 1555, the walls were whitewashed to cover the Catholic imagery of the murals. The interior was rebuilt to serve Protestant Holy Service, with pews in ordered blocks and a pulpit in a dominant position. Instead of the images of saints that had brought a colourfulness to the interior, the walls were filled with epitaphs of wealthy merchants and clergymen.

The same ease with which Catholic churches could be converted to Protestant purposes could also work the other way round. Some churches, built in Catholic times and later reformed, were reconverted into Catholic churches in the 20th century, for example St James’ Cathedral in Riga, and many churches in Pomerania.

In Pomerania we also find this example of a church that was built as a Protestant house of worship, but in the late 1940s converted to a Catholic church. It is the former manor church of Kulice (Külz) manor near Nowogard. The church was erected on the grounds of the Bismarck family estate in 1865. Pomerania was then predominantly Protestant and German-speaking. With the changes after the World War II, Germans were compelled to leave the territories east of the Odra, and Catholic Poles moved in, often forcefully evacuated from parts of Poland that were annexed to the Soviet Union.

Sweden’s hopefully last civil war was fought in 1598. The Swedish King Sigismund (also Sigismund III of Poland and Lithuania) was challenged by his own uncle, Duke Charles. The decisive battle was fought at Stångebro near Linköping on 25th of September, 1598. It was a victory for Duke Charles, and Sigismund fled Sweden. Gruesome and seemingly endless wars between Sweden and Poland followed. In Sweden, Duke Charles had several noblemen executed, whose only crime was that they had been loyal to their rightful king.

At the battlefield, a monument was erected in 1898. The inscription speaks neither of civil war nor of rebellion, but says that “Hereditary liberty and Evangelical-Lutheran faith were saved for the people of Sweden”. It is however dubious whether traditional liberties or the religion of the majority of Swedes were actually threatened by the rule of King Sigismund.

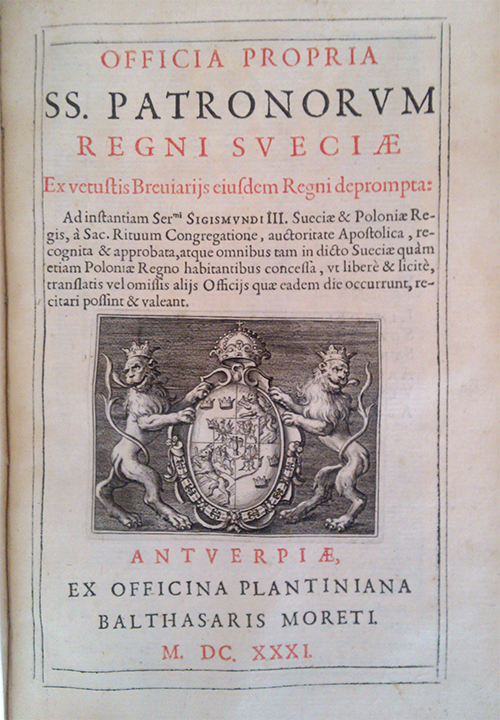

After the defeat of King Sigismund in 1598, a number of Swedish Catholics left Sweden for Poland together with the king. Here, they venerated the traditions of their old homeland. Copies of the Breviarium Romanum printed for Poland (1631) included an appendix with the Patron Saints of the Swedish Kingdom, who were no longer venerated in their homeland. In the coat of arms of the Polish kings of the Vasa dynasty, the Three Crowns and the Lion, symbols of the Swedish kingdom, are combined with the Polish Eagle and the Lithuanian “Vytis”.

Peder Laurensen, a Malmö reformer in 1530.

- They hinder the truthful Evangelical preaching in all countries and realms among the poor commoners, whom they keep chained under their old customs and ungodly, man-made services with ties, intimidations, taxation, imprisonment and distress. All of this income and profitable custom does not serve the praise and glory of God, not good Christian manners, but only their own bodily winning and the damage and oppression of the poor.

- - Peder Laurensen, Malmö 1530, quoted after Martin Schwartz Lausten. Reformationen i Danmark. 2016. Pp. 87–88.

Malmø-bogen (1530) was printed in the then-Danish town of Malmö, and exposes the ideas of the Reformation as conceived in an urban environment.

- We would truthfully say, that a poor man, boy or girl, who sits on a dung-wagon, and sings the ten commandments of God, or another Biblical hymn of praise to the glory of God; he or she is better and more worthy in the eyes of God, than numerous priests, monks or canons, who stand from morning until evening, murmuring and claiming without the right Christian faith or godliness, uncaring of what they are saying, singing or reading.

- - Malmø-bogen, 1530, fol. 42r/v.

- A hospital and a general house shall further be arranged for the help and repose of poor, sick, very old, and disabled persons, with honest service and care, from the funds of altars, guilds, and other wrongful uses, which have been practiced in the past.

- - Malmø-bogen, 1530, fol. 78v.

- We would not throw images or paintings away or hold them in contempt, as long as they are not used in other ways than the Christian way we have said here. But neither would we honour them with genuflexions or useless costs in the form of candles, clothing, offerings, gold, silver or money. But such should duly be given to God’s living images, our poor brothers and sisters, concerning whom we have God’s directions and commandments to donate and give clothes and food, such as we do not have considering trunks, stones, and lifeless, man-made images.

- - Malmø-bogen, 1530, fol. 103v.

Martin Lipp (1854–1923), a Lutheran pastor, poet and historian composed a first church history in Estonian, which reflects on the arrival of the Reformation to Livonia:

- And Knöpken came. And the arrival of this modest teacher became much more important than the arrival of ten Knights or bold Archbishops on their war horses or festive carriages into the capital of Livonia.

- - Martin Lipp. Kodumaa kiriku ja hariduse lugu. Jurjew, 1897.

Niels Kærgård’s Hvorfor er vi så rige og lykkelige? (Why are we so rich and happy? is one of several books in a series targeting the general public in Denmark in view of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. In this 71- page book, the point of departure is the question whether there is any connection between the opulence and general quality of life in the Northern welfare states of today and the fact that these countries were all affected by the Lutheran Reformation. Not surprisingly, Kærgård, Professor of Agricultural Economics at Copenhagen University, does not present any simple answer to the questions asked, but rather helps formulating these in a more qualified manner.

The Chronicle of Dionysius Fabricius, who clearly had Catholic sympathies, written in Livonia at the end of 16th or the beginning of 17th century.

- And what else should one wonder - that the seeds of that most unfortunate heresy were sown first in the year 1538, in Tartu, not in Riga, Tallinn or any of the Livonian port towns, also the head of the church Hermann Bay was present. And this was not done by some educated man, but a furrier, simple and crude, named Michael, who had come to Livonia from Nürnberg, sent by I do not know whether by God or someone else as the harbinger of the Devil.

- - Dionysius Fabricius. Liivimaa ajaloo lühiülevaade. Dionysii Fabricii Livonicae historiae compendiosa series. Johannes Esto Ühing. Pp. 162-163.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- What does the word “Reformation” mean to you personally / based on this article and the sources?

- A world/Europe torn apart?

- A necessary tool of modernisation?

- A return to true religion? Departure from true religion?

- An event in the past with no relation to the problems we are facing today?

Further reading

- Die Baltischen Lande im Zeitalter der Reformation und Konfessionalisierung: Livland, Estland, Ösel, Ingermanland, Kurland und Lettgallen: Stadt, Land und Konfession 1500–1721. Teil 1–4. Ed. Matthias Asche, Werner Buchholz and Anton Schindling. (The Baltic lands in the period of Reformation and confessionalisation) (Katholisches Leben und Kirchenreform im Zeitalter der Glaubensspaltung 69–72). Münster, Aschendorff, 2009–2012.

- Kęstutis Daugirdas. “The Reformation in Poland-Lithuania as a European Networking Process”. In: Church History and Religious Culture, vol. 97:3–4 (2017), pp. 356–368.

- Martin Schwartz Lausten. Reformationen i Danmark (The Reformation in Denmark). 4. ed. København, Eksistensen, 2016.

- Ingė Lukšaitė. “The Reformation in Lithuania: A New Look: Historiography and Interpretation.” In: Lituanus: The Lithuanian Quarterly, vol. 57:3 (2011), pp. 9–31.