1.18 Alcohol Consumption and Temperance Movements

Jörg Hackmann, Janet Laidla, Vitalija Kasperavičiūtė, Anne Sørensen

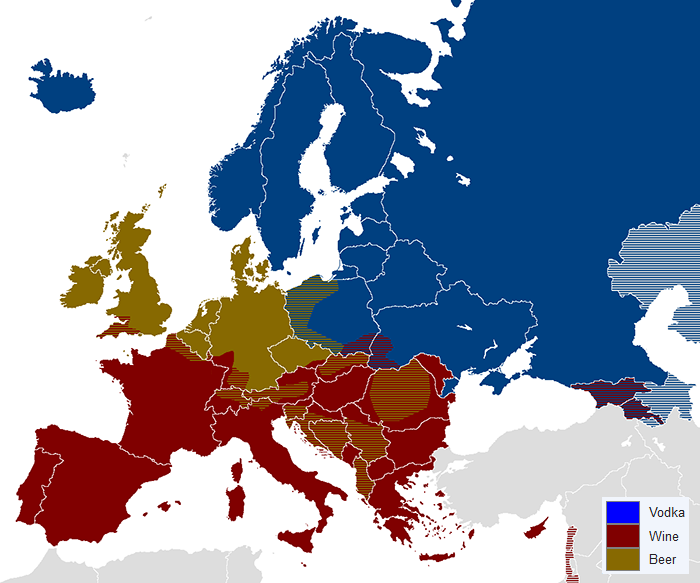

From a post-1945 perspective, the history of alcohol consumption and the fight against alcoholism seems to divide the Baltic Sea region into distinct parts: The countries of Northern Europe have been shaped by a strong public advocacy for sobriety and the limitation of alcohol consumption, whereas in socialist Eastern Europe unrestricted consumption and even partially politically motivated distribution of alcohol prevailed.

If we look into Baltic or even European history, however, we see a totally different picture: In fact, production of vodka from grain had become a source of income much earlier, and the demand for spirits rose with urbanisation.

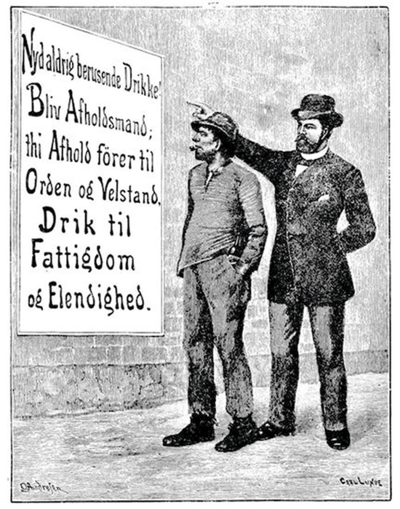

The food crises of the early 19th century as well as the North American temperance movement (think of Alexis de Tocqueville’s description) supported the idea that people should not drink liquor. The protagonists of this movement were mostly clergymen – Protestant as well as Catholic and later also Orthodox. As an appropriate form of the movement, voluntary associations were suggested and the bylaws were copied from American models. In the first wave, the kings and tsars were asked to organise such associations, but in the second half of 19th century, broader social groups stimulated a second, more radical wave of teetotalism, which in Northern Europe was supported by the Good Templars (IOGT).

In 1858, Lithuanian bishop Motiejus Valančius initiated a temperance movement based on similar movements in other Catholic regions (Silesia for instance). Within just a few years, over 80% of Catholics in the diocese belonged to these temperance societies. Lithuanians stopped drinking vodka, farms became wealthier, families became stronger, and people became educated.

Swedes were probably the most radical in battling alcohol consumption, although only the Finns introduced prohibition for a few years following World War I. Prohibition in Finland failed, however. “The Finnish bridge” was a name for the illicit movement of alcohol from Estonia to Finland in the 1920s during Finnish prohibition. There were many cartoons in newspapers and journals illustrating this phenomenon.

“The Finnish Bridge” was a famous slogan of the period of Estonian nation-building. It implied that the Estonians should follow the model of culturally and politically more advanced Finns. During prohibition in Finland, a large-scale alcohol smuggle was organised from Estonian territory.

The situation in the other countries faced similar obstacles: The attempts to reduce alcohol consumption stimulated various counter activities. University students and the consumption of alcohol have usually walked hand-in-hand. However, in the 1920s, the sobriety movement among the students of University of Tartu was influential enough to have alcohol banned from the official events of the Students Union. More resistant were the student organisations, although there were members of the sobriety movement who were literally counting and reporting the number of bottles of beer delivered to different student fraternities.

One of the members of the sobriety movement, Karl Parek, spied on male Student organisations to find out how much alcholol they consumed and worte his bachelor s thesis on the subject.

| Student Organisation | Crates per day | Crates per month | Cost per month | No of members | Liters of beer per member |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonian Student Society | 4.5 | 135 | 540 kr | c. 300 | 4l |

| Fraternity Fraternitas Estica | 1.5 | 45 | 160 kr | 84 | 5.3 l |

| Fraternity Sakala | 2.5 | 75 | 300 kr | 52 | 14.4 l |

| Fraternity Ugala | 2 | 60 | 240 kr | 78 | 7.7 l |

| Fraternity Vironia | 4 | 120 | 480kr | 93 | 12.9 l |

The tensions between drunkenness and sobriety are also highly political. The “mineral secretary” Gorbachev’s unsuccessful fight against alcoholism gave unintended support for instance to the Baltic independence movements.

Today, some members of Neo-Pagan Movement in Lithuania encourage their members to refuse any kind of alcohol. They reject the place of alcohol in traditional Lithuanian culture, leading to disagreement among members of Pagan community. Members of this order are trying to push the beer and mead drinking tradition from the pagan rituals.

Fragment from Johann Heinrich Zschokke. Die Brannteweinpest. Eine Trauergeschichte zur Warnung und Lehre für Reich und Arm, Alt und Jung (The Plague of Spirits. A sad history as warning and advice for the rich and poor, old and young). Aarau 1837.

The Swiss writer Zschokke suggests in his semi-fictional text, which highlights the bad consequences of alcoholism, to form temperance associations as a remedy and includes an example of bylaws for such a society that could be directly transferred from fiction into reality. This is not astonishing, because Zschokke followed the suggestions by the American reverend Robert Baird, who in those years tried - with some success - to convince the kings and in the Baltic sea region, including the Russian tsar, to set up national temperance societies. Fragments or even the whole books by Baird’s and Zschokke were translated in many languages around the Baltic Sea, in Estonia F. R. Kreutzwald adapted Zschokke to the world of Estonina peasants.

- The Statutes of the Temperance Society

- Now we deliberated the bylaws of the new society. They are simple. I drafted them – with a few changes we deemed appropriate – from the bylaws found in America and England. Here they are:

- We, the undersigned, who have learnt from miscellaneous accidents and misfortunes and are now convinced that the vice of drunkenness is indeed one of the most abhorrent vices before God and Man, and that drinking any manner of spirits in particular ruins the health; spoils body and soul; causes idleness and lust, poverty, strife and quarrelsomeness; and even precipitates serious crimes: - We have solemnly joined together with all our household in a Christian temperance union and pledge before the face of God and in the presence of our fellow man to keep the following vows in good faith:

- ‘Article I. We declare and pledge from this day forward to not drink spirits of any kind; nor allow wife and children to partake of the same; nor to give them to those who are under our command, in our service or employ; nor to trade or sell them; but rather to encourage our friends and acquaintances to abstain from this poisonous drink entirely.’

- ‘Article II. We declare and pledge from this day forward not to keep the company of knows drunkards, be it in public houses or other public places, and to immediately leave any place where, because of inebriation due to wine, beer or spirits, a man has lost the use of the reason granted him by God.’

- ‘Article III. We declare and pledge that we grant the Christian Temperance Union the right to expel from the community any of us who does not fulfil the above promise and also to name such persons as waywards.in our public gatherings.’

- ‘Article IV. A public gathering of the Society shall be held once per year where the President and Secretary, along with a selected committee of nine members elected to represent the Union’s business, shall report in detail on the progress of this Christian association.’

- ‘Article V. Anyone wishing to join the Society may do so at any time by submitting his name to the President or Secretary.’

State prohibition of alcohol consumption was a widely spread demand of the global abstinence movements since the late 19th centuries. The most famous case is that of the USA, where prohibition lasted from 1920 until 1933, but it was also introduced in Finland and Norway, and also in Russia after the begin of World War I. All these prohibition laws, failed however. In Sweden, the referendum for prohibition failed in 1922, but the state monopoly of alcohol sale has remained until today.

One of the social problems connected to alcohol abstinence was the challenge of creating an atmosphere for socialising without consuming alcohol. So cultural programs, excursions, tea rooms, libraries etc. were organised by temperance societies.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Discuss the accuracy and relevance of the single “alcohol belts” on the map.

- Do you think there is a common attitude towards alcohol consumption in the Baltic Sea region?

- Why did people gather in anti-alcohol associations?

- From a historical perspective has prohibition been successful?

- What is the attitude towards alcohol in your country today? How has it changed in history?

- Temperance movements have sometimes been seen as schools of democracy. In what way could they play such a role, in your opinion?

Further reading

- Sidsel Eriksen. “Drunken Danes and Sober Swedes? Religious Revivalism and the Temperance Movements as Keys to Danish and Swedish Folk Cultures.” In: Language and the Construction of Class Identities: The Struggle for Discursive Power in Social Organisation: Scandinavia and Germany after 1800. Ed. by Bo Stråth. Göteborg: Dept. of History, Gothenburg Univ., 1990. Pp. 55–94.

- Villem Ernits. The abstinence movement in Estonia. Tartu 1927.

- Mark Lawrence Schrad. “The Transnational Temperance Community.” In: Transnational Communities: Shaping Global Economic Governance. Ed. by Marie-Laure Djelic and Sigrid Quack. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2010. Pp. 255–280.

- Mark Lawrence Schrad. Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State. New York, Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Irma Sulkunen. History of the Finnish temperance movement: Temperance as a civic religion (Interdisciplinary studies in alcohol and drug use and abuse 3). Lewiston, Edwin Mellen, 1990.