1.14 The Baltic Provinces of Latvia and Estonia under Russian Rule during the 18th Century

Mati Laur, Valdis Teraudkalns, Alexandr Filyushkin

According to popular tradition, there are different ‘periods’ in Estonian and Latvian history: the Danish, the Teutonic Order, the Polish, Swedish and the Russian periods. The last period lasted two centuries following conquest of Livonia and Estonia by Russia during the Great Northern War (1700-1721). The administrative area of the province Estonia consisted of the northern part of today’s Republic of Estonia, while the province of Livonia was composed of the southern part of today’s Estonia as well as the northern part of Latvia plus also the city of Riga.

It is significant that the Baltic was conquered by the Russian Empire as part of the Swedish Empire. It was regarded as a former province of Sweden, and in the distant past, German land. Estonians and Latvians in the 18th century were not considered by the empire as independent peoples. They were defined as former German and Swedish subjects, and now – Russian subjects. The German Baltic nobility became the mainstay of Russia in the Baltic States.

The military conquest of the Baltic states by the Russian army was complete by 1710, when Riga and Tallinn were taken. The administrative structure of the Baltic lands in the Russian Empire in the 18th century was complex.

In 1796, after the third division of Poland, three provinces were formed in the Baltics which existed throughout the 19th century: Livland (Livonia, in different geographical boundaries from the medieval Livonia), Estland (Estonia), and Kurland (Curonia).

Russian power, the German ruling class together with the dominant Protestant Church, and the indigenous population of Estonians and Latvians, mainly serfs, made up a colourful and contradictory composition in the Baltic Region after the Great Northern War. There remained a far-reaching autonomy under Russian rule, supported by the German-speaking Lutheran upper class. The fully developed administrative order and well-organised officialdom introduced by the Swedes remained in force. During the 18th century, there were two opposing streams of thought in the administration of Livonia and Estonia: one the one hand, the German-Baltic nobility striving to maintain and widen their hitherto status provincialis, and on the other hand, the Russian authorities who were keen to integrate the Baltic more fully into the Russian Empire in order to unify the administrative system.

With the spread of Absolutism during the reign of Catherine II, pressure on the Baltic provinces intensified. The Baltic autonomy clashed head-on with the Empress’ desire for more power; her aim was to introduce a system of progressive laws in the whole of her empire without taking into account the national, religious or geographical characteristics of the people. With the end of Catherine II’s reign, a period of stalemate began between the Baltic provinces and the Russian central government still intent on a more complete integration of the Baltic into the Russian Empire but not yet in a position to annul the autonomy overnight.

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), one of the most influential German writers and thinkers during the Enlightenment:

- Livonia, you province of barbarism, luxury, ignorance and presumptuous taste, of freedom and slavery, how much needs to be done, to be done in order to destroy the barbarism and to wipe out ignorance and then to be able to spread culture and freedom.

- - Johann Gottfried Herder. Journal meiner Reise im Jahr 1769. Ed. by Karl-Maria Guth. Berlin, 2013. P. 15.

- In Livonia I lived so freely and uninhibited, teaching, working as though I would never more be able to live, teach and work.

- - Johann Gottfried Herder. Sämtliche Werke in vierzig Bänden, Bd. 40. Stuttgart, Tübingen, 1853. P. 127.

Catherine II (1729-1796), Empress of Russia from 1762, a leading figure during the period of enlightened Absolutism.

- Little Russia, Livonia and Finland are the provinces which have been ruled according to the privileges we bestowed on them, and to violate these privileges would be extremely imprudent. To treat these provinces as foreign countries, to regard them in this way would be a great mistake and completely stupid. These provinces have simply to be made to feel Russian and to cease being like wolves preferring to roam the forests.

- - Сборник Императорского Русского Исторического Общества, Vol. 7. Sankt Petersburg, 1871. P. 348.

- You have German, Polish and Swedish laws and cannot deny that the judges have distorted the laws for their own convenience, but you are now to be given laws that are good and honest so that everyone can be satisfied. You will be given laws like never before, never better ones, and I hope no one will prevent this happening.

- - Reinhold Stael von Holstein. “Die Kodifizierung des baltischen Provinzialrechts.” In: Baltische Monatsschrift 52 (1901). Pp. 185-208, 249-280, 305-358, here p. 272.

- It is not possible for the laws of Livonia to be better than ours, since ours were written with human love, and they cannot prove that theirs are like ours, while some of their laws are barbaric and unedified [ ... ] If they wish to express their solemn reservation, we would request our desire to keep the death penalty and torture and would ask that our justice never has to be administered by first having to battle against intrigue and subterfuge. We reserve the right to keep the contradictions and irregularities within our legislation etc., whatever other more enlightened people around us might think of such madness.

- - Alexander Brückner. “Die Verhandlungen der „grossen Kommission“ in Moskau und St. Petersburg 1767–1768.” In: Russische Revue 22. Sankt Petersburg, 1883. Pp. 325-356, 411-432, 500-541, here p. 507-508.

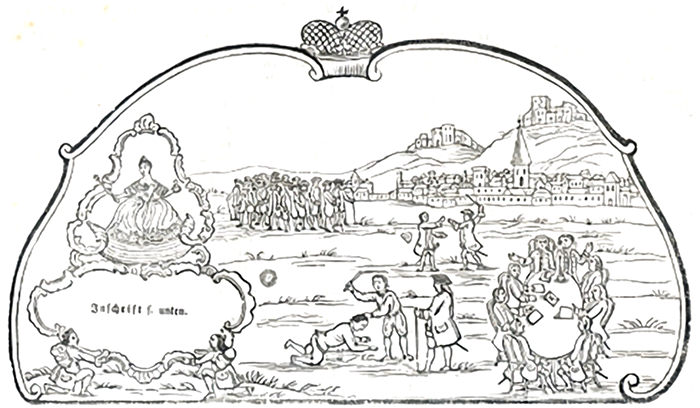

The banner of the citizens of the town of Dorpat (Tartu) during Catherine II’s visit in 1764.

- Most gracious Empress! We throw ourselves at your feet

- To savour homage and pity

- Because our council’s dignified justice

- Places a great burden on us

- Disunity and strife prevails its ranks

- Hence justice and politics are awry

- - "Illumination in Dorpat Ao 1764 bey dem Daseyn Ihro Kayserl. Majestæt Catharina II". In Sammlung verschiedener Liefländischer Monumente, Prospecte, Wapen etc. von Johann Christoph Brotze, Vol. 3, No. 107. Akademische Bibliothek der Lettischen Universität (Latvijas Universitāte, Akadēmiskā bibliotēka).

Sentiment of the Livonian District Administrators.

- As Your Imperial Majesty has, out of grace and charity which cannot be highly enough praised, in Your Highest’s own words has most mercifully deigned to preserve the rights and privileges of the land, and thus it is first and foremost those rights and privileges mentioned here and which are at the discretion of Your Most Merciful Imperial Majesty, which ostensibly cannot be reconciled with the some of the articles of the government administration introduced in Russia.

- These rights and privileges are, however, 1) that all governmental and court proceedings shall be held and recorded in the German language; 2) that all civilian offices in Livonia (excepting only the heads of government), shall be of German nationality, native to the land, and preferably of the Livonian nobility; 3) that all of our rights, courts, statutes and customs brought with us shall remain unchanged and 4) that the most precious of these privileges have Your Imperial Majesty’s highest assurance that of all that which Your glorious ancestors bestowed upon us, shall not the smallest bit be taken away.

- - Friedrich Bienemann. Die Statthalterschaftszeit in Liv- und Estland (1783–1796). Ein Capitel aus der Regentenpraxis Katharinas II. Leipzig, 1886 [Nachdruck Hannover-Döhren 1973]. P. 62.

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Why would the Baltic German nobility want to keep their separate rights and laws in the Russian Empire?

- Why would the Russian Empire want to integrate the Baltic provinces more closely with the empire?

- Where is the balance point of respecting minorities rights and integrating them into the state as a whole? Is there an integration discussion going on in your country?

Further reading

- Baltische Länder. Deutsche Geschichte im Osten Europas (Baltic states. The history of Germans in Eastern Europe). Ed. by Gert von Pistohlkors. Berlin, 1994.

- Indrek Jürjo. Aufklärung im Baltikum. Leben und Werk des livländischen Gelehrten August Wilhelm Hupel (1737-1819) (Enlightenment in the Baltic. Life and Work of the Livonian Scholar August Wilhelm Hupel). (Quellen und Studien zur baltischen Geschichte, 19). Köln, Weimar, Wien, 2006.

- Mathias Mesenhöller. Ständische Modernisierung. Der kurländische Ritterschaftsadel 1760-1830 (Modernising a Social Stand. The Nobility of Curonian Ritterschaft 1760-1830). Berlin, 2009.

- Ralph Tuchtenhagen. Zentralstaat und Provinz im frühneuzeitlichen Nordosteuropa (The central government and province in the early modern Northeastern Europe), (Veröffentlichungen des Nordost-Instituts, 5). Wiesbaden, 2008.