1.16 Manorial Heritage in the Baltic Sea Region

Herle Forbrich, Ewa Romanowska, Janet Laidla, Anne Sørensen

The manor houses, i.e. the representative residential buildings of agricultural estates, characterise the area east of the river Elbe in Germany and can generally be found around the Baltic Sea. The agricultural estates were interconnected by family and economic ties and the manor houses were economic, legal and social centres in rural areas. This organisational structure was developed in the Middle Ages and Early Modern times. The peak of the estate economy was reached around 1800, before first laws for the liberation of peasants from compulsory labour were enacted. In spite of these social changes, lords of estates more or less retained their power in rural areas until the beginning of the World War I.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, a network of thousands of such estates existed in the Baltic Sea region. In their centres remained the mansions. As residences of the lords of the manor, they represented family history, social order and tradition. However, they were also increasingly perceived as symbols of a society marked by inequality and dependence. In the 20th century, national movements, social modernisation, socialist transformation and, finally, a new historical consciousness changed the significance of these places.

As a result, the estates experienced some considerable legal and economic changes. This development started with agricultural reforms after the World War I in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. It came to a head as a result of the World War II, especially in those countries in the Baltic Sea region that came under Soviet rule or under the influence of the USSR. There were manor houses that lost their traditional function as the residence of a family. In West Germany and Scandinavia, on the other hand, most of the mansions remained privately owned and traditionally used. However, here too, economic changes made adjustments necessary and families, for example, started opening their private houses for guided tours or events.

Today, manor houses around the Baltic Sea are experiencing comparable economic changes and the marketing of the houses to be rented for different purposes, such as weddings or as an event venue and their use in tourism is increasing. At the same time, many countries have had laws for the protection of historical monuments since the 1970s. Since then, the appreciation of the manor houses as a cultural heritage has increased. Today, every country in the Baltic Sea region faces the challenge of preserving manor houses as a cultural asset.

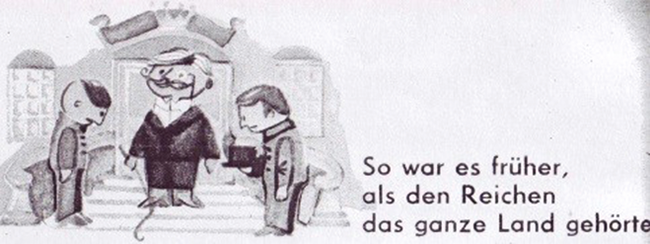

Two drawings illustrating the conversion of a manor house

They were published 1969 in the picture story “Sun, say how do you like our beautiful homeland?” in the magazine Bummi. Bummi was a children's magazine aimed at kindergarten children in the GDR and first appeared in 1957.

A song popular in Estonia

It appeared in the film Viimne reliikvia (The Last Relic, 1969) as Mässajate laul (Song of the rebels, music: Uno Naissoo/text: Paul-Eerik Rummo). The lyrics are based on a folk song that dates to the 1905 revolution during which a number of manor houses were burnt down in Estonia and Latvia.

- Song of the rebels

- Every man forges his own destiny.

- and creates his own happiness.

- Once he frowns in resentment at it,

- which the secret was behind it. Yes!

- The mansions are burning, the Germans are dying,

- The forest and the land will be ours.

- :,: For us yes, for us // For us, for us, for us. :,:

- Every man forges his own destiny.

- and creates his own happiness.

- Once he frowns in resentment at it,

- what the secret was behind it. Yes!

- The forests are burning, the land is dying,

- We're getting us

- :,: For us yes, for us

- For us, for us, for us. :,:

- Every man forges his own destiny.

- and creates his own happiness.

- Once - yes! -

- Well! -

- What's the secret behind it! Yes!

- We burn, we die,

- Then there's no slave left,

- No slave, no slave.

- No no master either

- ::: No slave, no slave

- No, no master either! :,:

Bornzin manor, 1860

Bornzin today is situated in the Polish voivodeship of Pomerania. The name of the village is Borzęcino.

Painting by Alexander Duncker (1813-1897). He was a German publisher and bookseller. His main work was a graphic collection of Prussian castles. Alexander Duncker. Die ländlichen Wohnsitze, Schlösser und Residenzen der ritterschaftlichen Grundbesitzer in der preussischen Monarchie. Band 8. Berlin, Duncker, ca. 1886. Digitalisiert durch die Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin, 2006. URL: https://digital.zlb.de/viewer/readingmode/14779821_08/187/LOG_0052/.

Primary school in Mäo manor in Estonia

After the land reform in 1919, many of the manors in Estonia were turned into school houses and some of them have remained schools to this day. With the support of several international grants, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Education and Research, the schools have been able to restore several of the manor houses and also develop a home page, events, books and worksheets for these schools to appreciate their unique learning environment.

The home page has some information in English – please look through it to gain more insight into this initiative: http://www.moisakoolid.ee/en.

Clausholm Slot: Wedding Ceremony at the Castle

In 1919, a new law removed the privileged status of manors and nobility in Denmark. This was seen as an implementation of democracy in terms of social status and a step toward economic equaliity – and as a way to prevent revolutionary uprisings like in Russia and Germany. In the following decades, economic distress and challenges for the manor houses followed. Since around 1960, many privately owned manor houses have developed new businesses in the experience economy. This involves cultural heritage initiatives, for example opening the manors and parks to the public, the founding of museums and the arrangement of concerts and fairs in the surroundings. In addition, new tourist sites have emerged, like safari parks and nature trails. Since around 2000, niche production of food products (locally based, organic, old species of grain, traditional recipes etc.) have also played a large role. Additionally, many of the manors have now been transformed to hotels, restaurants and conference venues, and ‘ordinary people’ can book a castle or a manor and may become ‘lord and lady of the manor’, for example for their wedding festivities. Clausholm Slot is a privately owned manor in the central part of Jutland, Denmark.

This text is from their web page, describing their offers for weddings.

- Wedding Ceremony at the Castle. Clausholm Castle provides a beautiful and historic setting for your wedding. By having your party or reception in Clausholm's event venue, you also get the chance to be wed in Clausholm's chapel. The chapel is an attraction in itself; its location on the second floor, with a view of the park and surrounding nature, makes a fantastic framework for one of life's great events.

- The chapel in the west wing of the castle has space for 95 wedding guests. The ceremony will proceed to music from the chapel's organ, which is famous among organists all over the world for its sweet sound. The chapel at Clausholm is consecrated, but without its own priest. We do have contact with an external priest and an organist who are happy to conduct weddings for payment. Because of the historical setting, it isn't possible to decorate the chapel. Throwing rice is also not allowed. You can be married at Clausholm's chapel from May to September.

- Wedding photos at Clausholm. Many couples choose to have their photo shoots in the romantic setting of the castle or park. The garden room (and certain rooms on the second floor) provide the backdrop for a classically beautiful wedding photo. The garden and the fountains, and the stately linden trees behind them, can make for sweet and natural pictures with a lot of character. While the pictures are being taken, the wedding guests can enjoy a nice walk through the park up to the event venue. You can also drive up for those who have trouble walking. An aperitif can be waiting for them at the top; this often makes for a smooth transition and good use of the time waiting for the bride and groom to come back from being photographed.

- - Cited from Clausholm castle web page, retrievable from https://www.clausholm.dk/

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Discuss the different messages the sources send about the manor houses in the Baltic area.

- Take the historical painting by Alexander Duncker as an example. What does this historical painting tell us about manors? Search for other paintings of manors and compare their message about manors/estates.

- The use of manor houses for education is widespread in Estonia. Find further information about this development and compare the situation with in your country. Which differences and similarities do you find?

- What is the message in the two drawings? Do you know similar pictures from your own country? With the development of public welfare in the 19th century, old buildings (in cities) were frequently reused for public services. Consequently, the use of manor houses as orphanages was not something completely new. But how was the situation really in manor houses or other old buildings that were used for public welfare?

- Read the lyrics to “Song of the rebels”. If you have a chance, listen to the song and/or watch The Last Relic. What is the message? What do you think about it?

- Find out more about a manor / estate in your hometown or in your neighbourhood. How is it used? Who is the owner? Who was the owner?

- Find out more about historic buildings in your hometown or in your neighbourhood that are not used for their original purpose, but have found new functions. Is the new function generally accepted? Talk with former and present owners. What do you think about it?

Further reading

- Małgorzata Jackiewicz-Garniec, Mirosław Garniec. Pałace i dwory dawnych Prus Wschodnich: dobra utracone czy ocalone? (Palaces and manors of former East Prussia. Lost or saved property?). Olsztyn, Cultural Community Association "Borussia", 1999. In German: Schlösser and Gutshäuser in ehemaligen Ostpreußen. Gerettetes oder verlorenes Kulturgut? Olsztyn, Arta, 2001.

- Lexicon of Warmia and Mazury, where 76 historical objects are described under the title Palaces and manors houses (in Polish): http://leksykonkultury.ceik.eu/index.php/Kategoria:Pałace_i_courts.